What do you mean by the “horizontal” and “vertical” dimensions of meditation?

The vertical dimension does not refer to body posture or to “transcending” to a “higher plane.” Rather it refers to becoming aware of subtler and subtler phenomena that give rise to coarser phenomena and ultimately suffering itself. And it refers to awareness moving from one kind of phenomena to a different kind of phenomena.

For example: while sitting in meditation I notice I’m thinking about how nice it would be to get up. Beneath these thoughts is aversion to the pain in my knee. Beneath the aversion is a sensation distinct from the aversion. These are “vertical” in that each is subtler than the previous and each is a different kind of experience: thought versus feeling tone versus sensation.

The horizontal dimension refers to a more common flow of similar types of experiences. We do this all the time in day dreaming: a thought about food leads to a thought about the grocery story; which leads to a thought about the car you used to drive; which leads to a thought about the car you’d like to own; which leads to the memory of reading an ad about that car; which leads to a memory of the beach you were sitting on when you read that ad.

In meditation we can spend a lot of time moving “horizontally” without much useful insight. The Buddha designed a practice that moves vertically from suffering to the different and subtler phenomena that spawn it.

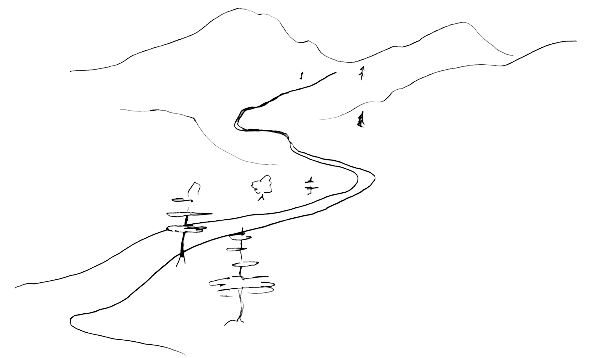

The Buddha said that the entirety of his teaching is summed up in Dependent Origination: every phenomenon is dependent on another phenomenon to bring it forth. Dependent Origination is often portrayed as a series of links chaining one experience to the next. Or it can be pictured as the flow of a river whereby water flows from one place to another down a more or less predictable channel.

For example, contact (raw sensation) flows into feeling tone (nice, not nice, neutral). Feeling tone flows into tightening (desire, aversion, or confusion). Tightening flows into clinging (experienced as simple thoughts). These simple thoughts flow into a series of thoughts, concepts, storylines, etc.

The Buddha said that wisdom and liberation arise from following this flow backward or upstream. Rather than waiting to see where our present experience leads, we look upstream to see where it came from. What caused it to arise? The Buddha called this the path of cessation: if the cause of an event ceases, the event does not arise.

While this may be true in theory, it may be confusing to practice. Let’s say I have a swirl of thoughts keeping me awake in the middle of the night. I’d love to have them all go away so I can sleep. So I look for the cause that gave rise to them in the first place: I try to think back to what was going on before the swirl began. Then what? I can’t make the past moment cease: the past has passed. I can’t change the past: it is gone already. I can think about it. But I’ve already got more thoughts in my head than I want. Analyzing my experience just gives rise to more thoughts when I’m trying to get the whole blooming mess to back off and leave me alone!

The practical implication of Dependent Origination may not seem as helpful. So many meditators give up and go back to the breath or choiceless awareness or something else they can experience in the moment. That’s what meditation is supposed to be about, right?

But now we are ignoring the Buddha’s other instruction to understand dependent origination!

So, I’d suggest a different approach to the present moment and dependent origination that is simple, practical, and deeply grounded in what the Buddha taught.

Think of dependent origination not as a spinning wheel, set of links, or even flow of a river. Think of it as a set of nested Russian dolls whereby each doll has a smaller doll inside. Each smaller doll is equivalent to an upriver link.

In other words, the tension that gives rise to the swirl of thoughts still exists in the present. It is “inside” the swirl. It is subtler and not as obvious as the colorful thoughts and images. What happened in the past to give rise to it is gone. But what keeps the swirls going is the tension that remains in this moment. That tension can be directly experienced now. And the more I feel it directly, the more it tends to relax. And as it relaxes, the thoughts run out of gas.

The vertical dimension of practice is sensing the subtler tightness inside the present moment and then releasing it. This takes us from the larger doll to the subtler one inside. And lo and behold, there’s another doll inside that one. It too can be released and opened.

This is what the Buddha recommended. It’s the path of release. It’s the “vertical” path in that it looks for the deeper source of the present moment that still exists in the present. Rather than move “horizontally” across the surface, we move “vertically” to see what’s “below” or “inside.”

This vertical movement is not analysis. It is intimately feeling the moment on it’s own terms. It feels like “relaxing into” the depths of the moment rather than standing apart and scrutinizing it.

The Six Rs are a precise way to practice this vertical movement or to open each successive doll. You can find a fuller explanation of the Six Rs in the first chapter and second chapter of my book: Buddha’s Map .

Copyright 2014 by Doug Kraft

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use all or part of it for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the author. Specific licensing details are here.

How to cite this document

(a suggested style): "Nested Dolls and Depth Meditation" by Doug Kraft, www.dougkraft.com/?p=VerticalMeditation.