Chapter from Meditator’s Field Guide copyright 2017, Doug Kraft.

I laugh when I hear the fish in the sea are thirsty.

During the 1990s I had a wise and wonderful psychotherapist who helped me work through the remainder of the depression that had haunted me since childhood. She had ways of looking at my inner dynamics that were new to me. Yet they often rang true. I came to trust that she had a deeper and more sympathetic understanding of me than I had of myself. Some of her insights shook me to the core. “Wow,” I thought, “I’ll never forget that.”

Yet I often did forget. Some insights never left. Others faded in a few minutes. For the life of me, I couldn’t remember what she’d said – only that it was important. “Can you say that again in as few words as possible so I can memorize it by rote?”

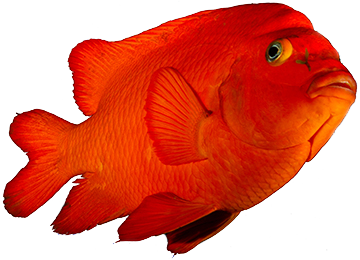

She’d laugh. “We found a slippery fish. Since they challenge your core character structure and beliefs, they are as difficult to hold onto as a bar of soap or a slippery fish. They are probably true, otherwise the mind wouldn’t push them aside so adroitly. We’re onto something valuable.”

I found similarities in meditation. Some insights resonated deeply and never floated away. Others rattled my core and faded like a dream.

When I began teaching, I was surprised to find the same phenomenon with yogis. I had to offer some teachings over and over like, “Meditation is not about getting rid of anything,” or “It’s not personal. Nothing is personal.” No matter how emphatically I repeated these, the next day or next week, I had to say them again. “Oh yes,” the yogi would say, “I forgot.”

I began collecting these slippery fish and reducing them to a few words so they’d be easier to remember. Traditionally they are called “gathas” – short phrases designed to illuminate the meditative process or spiritual understanding. Then I’d find images or stories to give them life.

My collection of meditative slippery fish is the core of this field guide. Each chapter is a reflection on one of them. Each chapter begins with a gatha. The gatha is either the chapter title itself or is displayed immediately after the title. The appendices include a list of them.

Some of the insights fade more quickly than others. But all reflect an essential meditation understanding that can slip away without so much as saying goodbye. I hope this field guide will help bring them back to life.

Each reflection is written to stand alone without the support of the others. They can be read in any order depending on your need and curiosity. However, a book requires a linear sequence. So I grouped the reflections into five sections:

Section I: Finding a Compass

Section II: Getting Our Selves Out of the Way

Section III: Glowing Like a Candle

Section IV: Cleaning Up Our Act

Section V: Expanding Infinitely

Organizing the field guide this way reflects how I’ve seen yogis travel the Buddha’s path. And it roughly parallels the Buddha’s descriptions of his Four Ennobling Truths and Eightfold Path. The chapter on "Three Essential Practices" and Appendix F explore the Four Ennobling Truths and the Eightfold Path in more detail. For now, let’s unpack the five sections of this book.

If we want to travel from New York to San Francisco and head south, it will be a very long journey, no matter how mindfully we take each step. On the spiritual journey, we must develop a compass — get our general direction — right from the beginning lest we wander aimlessly.

It’s especially important when we consider what motivates us to begin a spiritual journey in the first place. Today, as in the Buddha’s time, we’re less likely to feel drawn by lovely possibilities than to feel pushed by gritty realities we want to transcend, escape, heal, or alleviate. Sometimes the pain is obvious: illness, injury, loss of a job, death of a friend, or breakup of a relationship. Sometimes the pain is quiet: loss of meaning, vague dissatisfaction. As Aldous Huxley wrote, “There comes a time when one asks even of Shakespeare, even of Beethoven, is this all?”

In good times we may muse about peace, enlightenment, and spiritual realization. But usually it takes a wake-up call to get us to take the first step. That wake-up call is often some kind of pain or dissatisfaction.

Millions of years of evolution have bred us to flee pain. Pain jolts us to move us along. If the problem is a large predator, flight may be the best solution. But if the problem is internal anguish, the urge to tighten up and run away is not so helpful. As Buckaroo Banzai put it, “Wherever you go, there you are.”[1]

So the Buddha’s teachings begin with suffering and how to understand and deal with it effectively. He never said life is suffering. Only that suffering is a part of life . It’s woven into the fabric of the unstable world in which we live. Everything breaks, nothing lasts forever, and all that we love will fade eventually. Since we can’t always dodge suffering, it’s best to understand how the mind-heart responds to it and figure out how to engage it wisely.

It’s difficult to understand something if we’re avoiding, denying, ignoring, or trying to control it. Avoidance creates tension. To truly understand a difficulty we have to turn and face it. And since tension distorts our perception, we must first relax.

It’s not so easy to relax the mind and open the heart in the face of suffering. But if we don’t, we’ll have no wisdom to guide us.

The Buddha takes it a step further. If suffering is an illness, he said the disease is incurable. It’s inherent to life in this relative world in which we live. His solution was to get rid of the patient. If there is no one to suffer, there is no suffering.

His logic may be clear. But what it means to “get ourselves out of the way” may be mystifying in this context. It doesn’t sound like what we had in mind when we started on this path. We’d prefer improving ourselves, finding a true self, or realizing our highest nature. But as we engage this path, it gradually becomes clear that full awakening cannot happen until we see our self to be as ephemeral as a cloud in the sky or a sandcastle under a wave.

The Buddha called this “Wise View” (samma ditthi). In a nutshell it means seeing the impersonal nature of all phenomena. There is no permanent, enduring self-essence separate from everything else.

So the first section of this field guide, “Finding a Compass,” explores the challenges of turning toward difficulty, relaxing into it, and seeing the impersonal nature of all phenomena including the self. This is the compass bearing the Buddha offers.[2]

The second section takes this direction and puts it into practice. It’s about the actual techniques and attitudes that naturally soften tension and allow the ephemeral self to lose its illusion of solidity, like a mist evaporating in the morning sun.

The Buddha said the root of our experience of difficulty is a preverbal, instinctual tightening called tanha. He encouraged us to abandon this tension. He didn’t counsel us to turn away from suffering but to relax the tension it brings.

This leads to what he called “Wise Attitude” (samma sankappa): the attitudes and intentions that flow from seeing the impersonal nature of phenomena. These, in turn, lead to wise effort without strain, awareness, and stability of mind.

The section explores all of these themes: abandoning tension, relaxing the sense of self, effort without strain, cultivating awareness, and allowing the mind to stabilize itself. This is how we learn to get our selves out of the way.[3]

As we relax tension and give up on improving, fixing, preening, bolstering, or elevating our sense of self, we’re left with a mind-heart that glows. We find an awareness that is soft, clear, kind, wise, and wide open. Suffering fades into a sense of simply being with what is.

We still engage the conventional world, love our children, go to work, buy groceries, and discuss events of the day. But we don’t get thrown off balance as easily as before. And when we do, we recover more quickly.

This third section of the field guide offers tips to help us stay with this luminous awareness more easily and deeply.[4]

However, no matter what we do, the luminous, pure awareness doesn’t last. We touch something lovely outside of time itself. Then it fades. Peacefulness expands into spaciousness; then it collapses into a muttering, discursive mind.

With all its qualities, the glowing mind-heart can shine light on old wounds hiding in the shadows. Mark Twain remarked how self-knowledge is bad news. Old habits rise to the surface. Old neuroses get restimulated. Old ways of thinking disrupt equanimity.

Most of us spend a lot more time outside meditation than in it. The mind that grumbles in the rush-hour traffic keeps grumbling in the meditation hour. The strains of life play out in our practice.

Gradually it becomes obvious that meditation alone is not enough. We need to clean up our act. We need to get to work on what Ram Dass calls our “uncooked seeds.”

As important as it is to figure out how to engage life in the world, most of us do not need a code of ethics or list of precepts to know that it’s not helpful to kill, lie, steal, seduce the neighbor’s partner, or go on a drunken binge.

However, in the relative world, there are no absolutes. There are no rules that we can follow rigidly and always be safe. It’s these gray areas that throw us off.

So rather than lead you through specific precepts in separate short chapters, this section has longer but fewer chapters exploring the relationships between skillful behavior and wholesome mind-states. And it looks at the importance of kindness as an overarching guide.[5]

During the Buddha’s time, the most advanced societies had slavery or rigid castes; women were considered chattel; the world was thought to be flat; and science, religion, art, and ethics were fused in an undifferentiated mass. The scientific method would not emerge for two millennia. Modern psychology wouldn’t emerge for several centuries beyond that.

The people in the Buddha’s time weren’t stupid. Their brains were the size of ours. Many people had great wisdom. But the way the average person thinks about and understands the world has evolved dramatically since 500 BCE.

Were the Buddha alive today, he’d probably have a few new tools for us. He’d have other ways to help us get out of our way. In this last section we’ll explore one of those: the infinitely expanding self.

This book is a collection of reflections on the tips, hints, gathas, guides, and tools to deal with slippery fish found at many different stages of the journey toward kindness and wisdom.

I hope you will be inspired to write about your own slippery fish. Taking the time to articulate insights that slip away can deepen the investigation of gifts that otherwise fall back into the sea.

Before turning to specific slippery fish, I’d like to guide you through an exploration of who the Buddha was and how Buddhism first entered the world. Seeing the origin of these teachings and the people the Buddha was addressing can help us understand the depths of what he was trying to convey.

1. Buckaroo Banzai is the lead character in the 1984 film The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension, written by Earl Mac Rauch.

2. This first section relates roughly to the first of the Four Ennobling Truths (understanding suffering) and the first two folds of the Eightfold Path (Wise View and Wise attitude).

3. This second section relates roughly to the second of the Four Ennobling Truths (relaxing the tension that creates suffering) and the second, sixth, seventh and eighth folds of the Eightfold Path (Wise View, Wise Effort, Wise Awareness or Mindfulness, and Wise Collectedness (samadhi ).

4. This third section relates roughly to the third Ennobling Truth (realizing the well-being of cessation as discussed on pp. 7-12) and the last three folds of the Eightfold Path (Wise Effort, Wise Awareness, and Wise Collectedness).

5. This fourth section relates to the three middle folds of the Eightfold Path. The third fold is about how we communicate with one another (skillful speech). The fourth fold is about how we treat those around us (skillful actions). The fifth fold is about how we engage the world as we take care of ourselves (wise lifestyle).

Copyright 2017 by Doug Kraft

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use all or part of it for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the author. Specific licensing details are here.

How to cite this document

(a suggested style): "Slippery Fish" by Doug Kraft, www.dougkraft.com/?p=SlipperyFish.