Click here for a pdf of this reflection. Other reflections in the Inner Landscape series are:

1: Experience; 2: Vedana; 3: Dissolving Suffering; 4: Endearing; 5: Dependent Origination

My father was a marine engineer. During the middle segment of his career, he worked with a team of engineers designing oil tankers. He had particular expertise on the giant steam turbines used to propel these ships. He worked for Esso International out of an office in New York City. However he often traveled to Phoenix and Geneva where the turbines were built.

I was amused that the two places where engines for huge ocean-going vessels were assembled were about as far as one can get from the ocean: the Arizona desert and the Swiss Alps.

The technical papers, engineering specifications, schematics, and other documents coming out of Switzerland were in German. At that time, computers were beginning to be used for a growing variety of tasks. Someone wrote a program to translate these papers from German to English.

At first, the translations looked good. Some German syntax sounded awkward in English, but the documents were understandable. Except for one term. The translations kept referring to “water goats.” What was a “water goat?” No one knew.

They found an English-speaking engineer fluent in German and had him read the original papers. A “water goat” turned out to be a “hydraulic ram.”

Words have no inherent meaning of their own. They’re fingers pointing to the moon, not the moon itself. Words are verbal or graphic symbols pointing to a specific experience.

If you and I have similar experiences and agree to use the same word — let’s say “gwauk" — to refer to it, then that word is helpful. “Gwauk" points to something we both understand.

But even within a single language, words typically have a cluster of meanings and connotations. The same word may be used to point to very different experiences.

The bark of a tree has nothing to do with the bark of a dog. The bark of a dog has only a superficial relationship to the way the drill sergeant gives orders. And none of them have much to do with the peppermint bark I pick up in the candy store.

Still if we understand the meanings surrounding a word, we can usually pick the correct one from the context.

When we try to translate from one language to another, the process is even more complex. When my father told me about water goats, I understood for the first time that words do not have exact equivalents in other languages. The clusters of meanings and connotations are not the same in different languages. As far as I know, there is no single German word that points to the skin of a tree, the yelp of a dog, abrupt orders, and a kind of candy.

We can’t translate from German to English simply by finding the right English word for the German as if there is an exact equivalent. We can’t translate a Pali term into an English word by looking it up in a table of word substitutions. What we do with a wet goat is very different from what we do with a hydraulic ram. To call the sergeant’s orders “candy” is confusing at best.

Even if the translated word is kind of correct, subtle nuances can skew the meaning. For example, the English the phrase “come alive” is often metaphorical. The same phrase in Chinese is usually literal. When Pepsi started marketing in China, they used their very successful slogan, “Come alive with the Pepsi generation.” It translated into Chinese as, “Pepsi brings your ancestors back from the dead.” It was not very successful in selling soda.

While learning to meditate, we may seek guidance from a man known as Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha — perhaps the most gifted meditation teacher the world has known. He lived and died 2600 years ago in a different age, different culture, different economy, different world view, different class structure, and different consciousness. He spoke a language further from English than English is from German or Chinese.

His talks were not recorded in a language he spoke. As best we know, he spoke a dialect of Prakrit. Centuries after his death, his talks were first written down in the Pali language. Pali and Prakrit don’t have a word for “meditation.”

So when we turn to the Buddha for meditation guidance, we are looking for help in a process that he did not even have a word for! The Pali word used to translate the Prakrit word he used was “bhavana.”

Bhavana was an agriculture term. It describes what farmers do to their crops — caring for the soil and planting seeds. It might better be translated as “cultivation.” It was a common, everyday word that implied helping something grow in a natural way. It connoted support, nurturance, and care.

The English word “meditate” has a slightly esoteric tone — something done by special spiritual people. But “bhavana” was an earthy term familiar to farmers and peasants. It is organic and grounded in everyday life.

I’m not saying all this to discourage you — quite the opposite. It’s amazing how much we can learn from his guidance despite how far away he is in time, space, culture, worldview, and language.

But to get the most from what he says, it helps to not get caught up in nuances of English words. He did not speak English or Pali. English nuances may be irrelevant.

It helps to remember that states of consciousness and qualities of awareness are far subtler any words. It helps to remember the context of his life, who he was speaking to, what their concerns might have been, and what his words might have meant to them. It helps to look at our own experience and intuit what he might have been hinting at. And it helps to let our thinking be a little loose as we feel our way through his words and our experiences.

I’d like to talk about the inner landscape we engage in meditation. I’d like to discuss what we see when we turn our attention to our innermost mind-heart.

I’d also like to bring the Buddha into this conversation: what he might have to say about our experiences. We’ll look at the Pali terms and see if we can unpack what those words meant to the Buddha and to those around him.

I’d also like to bring science into this conversation. The Buddha encouraged us to look at our experience impersonally and objectively. Scientific language encourages us to think impersonally. I’ll consider some of what we’re learning from evolutionary psychology and the neurology of consciousness.

This will be a three-way conversation between our innermost experience, the Buddha’s commentary, and scientific observation.

To start the conversation, let’s consider what the Buddha thought was most important. He said, “I teach one thing and one thing only.” What was that? …

“Suffering and the cessation of suffering.”

Right away we have a problem: in English that sounds like two things. I think he was saying “I’m only interested in alleviating suffering. But we have to understand what suffering is before we can know how to alleviate it.”

The distinction is important. Buddhism can sound pessimistic because it focuses on suffering. The Buddha never said “Life is suffering,” only that life has suffering. He was optimistic about our capacity to ameliorate suffering. That was his main interest.

Since he was most interested in mitigating suffering, our first question is, “What is suffering?”

We might respond: hurt, pain, hunger, wanting, desiring, fear, stubbed toes, broken hearts, grief, failure, and so on.

Notice that none of these say what suffering is. We all experience it. Yet it’s so hard to define that we usually fall into describing its causes and giving examples.

The Buddha did the same thing. In the text, he doesn’t define suffering. Mostly he describes its causes and gives examples.

It’s like trying to describe the color green. We might call it “yellowish blue.” But that hardly conveys the experience. For me “yellow blue” brings to mind Cub Scout uniform with its blue shirt and yellow neckerchief: not helpful.

So we might say, “You already know what green is. You’ve experienced it. Green is the color of grass in the spring, leaves in the summer, bell peppers, the ‘go’ light on the traffic signal, banana leaves.”

This is more effective than trying to define “greenness” abstractly.

Here is a typical way the Buddha described suffering: “Birth is suffering; aging is suffering; sickness is suffering; death is suffering; sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair are suffering; not to obtain what one wants is suffering; in short, the five aggregates affected by craving and clinging are suffering. This is called suffering.” [1]

He’s saying, “You already know what suffering is. It’s what you experience with birth, aging, death, sorrow, …” and so forth. He gives examples.

Suffering is intangible in the sense that it doesn’t exist in physical three-dimensional space. It’s an inner phenomenon. It’s something we experience inside.

This begs a larger question: “If suffering is a kind of experience, what is experience?”

“Experience” is harder to pin down than “suffering.” Yet Buddhism is all about experience — the intangible inner landscape. Another way to approach the question is to ask, “Who experiences?” For example, do our pets have experiences?

It seems like they do. They seem to see, respond, remember, don’t like things, want things. Even fish sleep — have stretches of not having much experience – and later wake up and start having experiences. When I was a child dropping fish food into the fishbowl, they recognized what it was and swam toward it — they remembered, responded to stimuli, etc.

Let’s bring science into the conversation. First, a reminder of how we got here. We started with the question, “How do we alleviate suffering?” This led to the questions, “What is suffering?” It seems to be something we experience. This led to the question, “What is experience?” This is even harder to pin down. So we’ll turn to objective science to see if it can help.

Neuroscientists have a working definition of experience that is worth contemplating: “Experience is the tip of the iceberg of the flow of information through us.”

What does that mean?

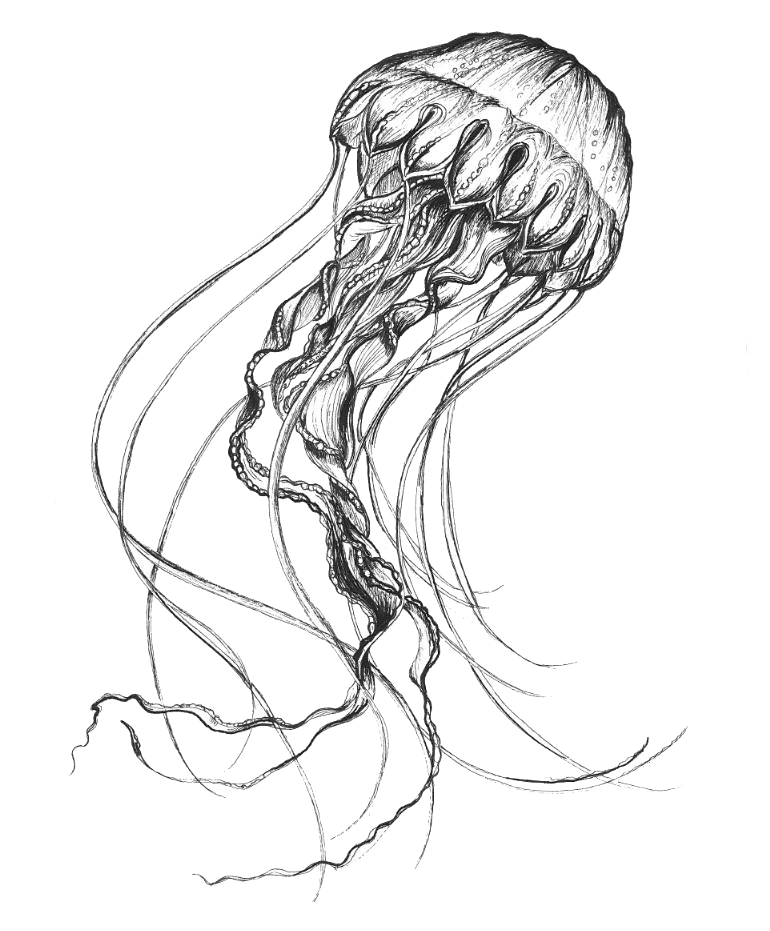

Five hundred million years ago, jellyfish were the most complex creatures on the planet. They had specialized cells: some cells sensed light, some cells “tasted” chemicals in the water, some cells were muscles.

They had to transmit the information about what “tasted” good or bad from the sensory cells to the motor cells that could move the jellyfish toward or away. They developed other specialized cells for transmitting information for one part of the organism to another. This was the beginning of neural tissue.

Today, our bodies transmit a vast amount of information

For example: 2 million cells in our bodies die every second. Every cell in the body is replaced at least once every 7 years. The body knows what to do about this. Various systems remove the dead cells and start new cells growing. This requires an ongoing exchange of information. Most is below the level of conscious experience.

What we actually notice consciously is a tiny fragment of all this information: sights, sounds, tastes, smells, touch, thoughts, moods, ideas, emotions, etc. Our nervous system does a lot to sort out and interpret information as well as pass it along.

Neural science says “experience” is the very top level of this transmission of information: signals that register consciously.

It’s hard to know if a jellyfish actually has experiences or is just a zombie responding mechanically to sensory information. But more complex creatures seem to have experiences. They have all the underlying physiological mechanisms that support experience in us.

Crawfish and shrimp, for example, can be trained to move toward or away from various stimuli. To do this they must sense things, remember them enough to associate them with other things, and act on that information.

Maybe they are zombies. But it seems like they experience something. And their experience is based in this flow of signals through their systems.

When I first heard the psychologist, author, and dhamma student Rick Hanson, talk about this, it made sense to me. [2]

Other examples of experience include seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, tasting, thinking, yearning, reminiscing, worrying, planning, dreaming, and so on. Even the thoughts we act on or not are the results of the processing of lots of information.

Now let’s bring the Buddha back into the conversation. He divided this flow of signals — i.e. “experience” — into what he called “Khandhas.” Khandha literally means: aggregate, heap, cluster, loose pile of similar kinds of experiences. I call them “clusters of kinds of experience.”

There are five kinds of khandhas. Everything we experience falls into one of them. We can use them to map our internal experience in meditation or anywhere in life. They underpin this thing called “suffering.”

What’s important is not the labels but recognizing the states in our own inner experience. What are the phenomena these words point to?

The Pali term for the first khanda is rupa. Rupa refers to a living, energetic, animate body with working sensory organs. Khya is a Pali term referring to the physical aspects of the body: bone, blood, tissue, etc. A khya can be a corpse. But rupa refers to a live body with operating senses. A dead khya is an oxymoron. So while rupa also means “body,” here it also connotes the senses through which we know the body: seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, feeling, thinking. Rupa is raw sensation.

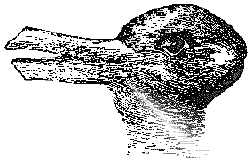

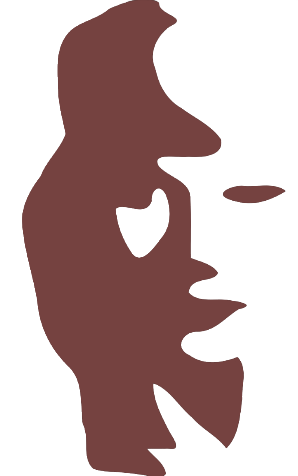

Optical illusions, like the ones show here, can help us distinguish rupa from the other khanda. Is the first a duck or a rabbit? Is the second Bill Clinton playing a saxophone or Monica Lewinski? Is the third an old cowboy or his son?

As you look at these images, what you think you see can change quickly from moment to moment. But the actual light patterns striking your retina do not change. The light patterns are rupa — the raw sensations themselves. Our interpretation is a different khanda that we’ll get to shortly.

The second khanda is vedana. Even though it is often translated as “feeling tone” or just “feeling,” it is not emotion. Emotions are more complex involving other khandas. Vedana is just pain, pleasantness, or neither. It is a component of emotion along with thoughts, beliefs, ideas and more.

Classically vedana comes in three types painful, pleasant, and neither-painful-nor-pleasant. However there may be more than three kinds of vedana.

As you view the three illusions, read these words, gaze out the window, or listen to the nightly news, you may experience different feeling tones.

There is not a lot about vedana in the text. But I’ve become convinced that it’s crucial to mature meditation and a rich life. I will go into this in more detail in the second reflection in this series.

The third khanda is sanna or perception. In Buddhism perception implies putting a label or a concept on our experience

The meditation teacher and author Stephen Levine described taking some ornithologists on an excursion through a wildlife sanctuary. Stephen didn’t know much about birds. One of the scientists said, “Oh look. There’s a vermillion flycatcher.” Stephen said he could feel his experience change from a delightful, purple streak of aliveness to a dense “vermillion flycatcher.” His mind tightened as the label covered and replaced the living experience.

Labels are real and can be directly experienced. But the labels themselves are not the content of raw experience. They are pointing fingers, not the moon itself.

Illusions demonstrate how sanna can change while the rupa remains unchanged. The following scrambled letters also illustrate how what we physically see (rupa) can remain the same while the sanna changes:

Msot poelpe are albe to raed wrods as lnog ecah wrod has all the right letrtes and the frsit and lsat ltteres are in the rgiht pacels. Erevy tihng esle can be mexid up. I’ts aznimag how esialy the mnid oargneizs the rset itno fiaimalr pternats and maeinng. Tihs sohws the dernfiecfe beweetn rpua khnada (raw sasoientn) and snana khnada (prepcptnio). Rpua cahnges while snnaa sayts the smae.

The khandhas interact with each other.

Joseph Goldstein tells a story that illustrates the complexity of these interactions:

A couple moved into a new house. The first morning in the house, they woke to the sounds of birds chirping in their basement. They heard them on and off through the day and concluded the birds had a nest down there.

They were delighted. It felt like a blessing to have these woodland creatures take up residence with them. They decided to stay out of the basement lest they scare them off before the babies were grown.

However, a few days later, they had to go down to the basement to tend to something. The husband tiptoed down as unobtrusively as he could. He quietly looked around for the birds or their nest.

He saw nothing.

Then he heard a loud chirp. He turned around. He wasn’t looking at a bird at all. He was looking at a smoke detector. It chirped again.

The squawking of the defective smoke detector was so annoying that they called an electrician to come out as soon as possible and fix the darn thing.

The actual sound they heard (rupa) did not change. But their perception (sanna) as chirping or fire alarm did change. The feeling tone (vedana) changed based not on the sound (rupa) but on the perceptual interpretation (sanna) of the sound. This illustrates that the same raw sensation (rupa) can have very different feeling tones (vedana) depending on its label (sanna).

The fourth khanda is sankhara. It’s a complex term with many different meanings. Loosely, it refers to thoughts, concepts, beliefs, stories, mental constructs, and ideas.

The term itself literally means something that has been pushed into form. “Khara" means “action” and “san” implies some extra push in those actions. It’s about something being formed or molded.

In Pali, the implication is that something that is formed is fragile. It can easily fall apart. The songwriter Paul Simon wrote “Everything put together sooner or later falls apart.”

Since it’s about something being formed, one common translation of sankhara is “formation.” However in English, “formation” sounds like a rock formation. It implies permanency.

Another increasingly popular term is “fabrication.” But that implies intentionality which may not always be true.

Evolutionary survival favors thinking — we were scavengers for whom mapping out the world around us was very helpful. Primate children love to play and pretend.

So when there is any stress in the system, either positive or negative, the brain wants to mull it over or figure it out. We end up focused on what we are thinking about and miss the experience of thinking itself. Nevertheless, thoughts do have pre-verbal feeling tones, textures, and moods which we can learn to see.

“The Room of Thought” is an exercise that illustrates thought as an experience in and of itself separate from its content. It goes like this:

Close your eyes and relax for a few moments…

Imagine a room with two doors, one at either end. You are standing in this room near a wall so that you are about equal distance from each door.

Your thoughts come in one door, move through the room past you, and go out the other door. Take a few minutes to just watch the flow of thoughts as if they were visible in this room… Notice what they look like… Notice how they move… They may come in different sizes, shapes and colors… Some may zip through quickly while others saunter along… Some may float while others trudge…

Now the exit door closes. Thoughts can enter but can’t leave. See how this affects them and what happens in the room…

Now the entrance door closes. Thoughts cannot exit and new thoughts can no longer enter. See what effect this has. …

Now both doors open so thoughts can both enter and leave. Observe what happens now…

One thought slows down, stops right in front of you, and looks you over carefully. See what this is like…

Now image switching places so that you are no longer you observing a thought but you are the thought observing you the person. What do you notice about your self?…

Imagine switching back to being you watching the thought. Has it changed through the experience?…

Now let the scene return to “normal” with you watching your thoughts move into and out of the room of awareness.

What’s important in relating to thoughts in meditation is to notice the process of thinking, planning, conceiving, imagining, etc. apart from the content of the thoughts, plans, concepts, images, etc.

Peaceful thriving requires unmasking the thought to see them as they are and relaxing the tension that is used to grab our attention.

The final khanda is vinnana or consciousness. Consciousness has two different meanings in English: (1) how we interpret awareness and (2) awareness itself.

How we interpret awareness is effected by contact (phassa) between a sensory stimulus (like light), a sensory organ (like the eye), and a sensory awareness (like seeing). It can also be affected by all the other khandas. So this kind of vinnana is conditioned. It includes all the other khandas within it.

I think the second understanding of vinnana as awareness itself is a better understanding of this khanda. So I prefer to call it “knowingness,” “awareness,” or “pure awareness” that has no agenda.

Here is an exercise that illustrates and sorts out these various meanings.

Take a few moments to settle into a quiet space…

Now place your awareness on your foot. See what you notice…

Now place your awareness on the places where your body touches the chair…

Now bring you awareness to the sensations of the breath…

Notice the sounds from the street…

Notice the temperature of the room…

The colors on the walls…

Let’s pause for a moment.

Were you aware of your foot in the few moments before I mentioned it? Probably not. The foot was there. It followed you into the room. But subjectively it was not there until you put your attention on it.

This illustrates that awareness has two aspects. One is the object — the foot, the body where it touches the chair, sounds, etc. And the other is awareness itself. Without awareness, you would know nothing of your foot, the sounds from the street, the pictures on the wall.

However, our evolution bred us to attend to the objects and ignore the awareness. To survive in a difficult situation it’s more important to know the environment than the awareness itself. This is why it is easier to focus on an object, like the sensations of the breath, rather than awareness itself.

To thrive rather than merely survive, we need to be aware of the awareness. Meditation is not about the object. It’s not about the breath, a mantra, a feeling of metta, a kōan. It is about awareness itself. It's about seeing the qualities of the mind-heart and how they shift and change.

How do we do this? To illustrate, let’s continue with the exercise:

With your eyes open, let yourself settle in again for a few moments…

Now be aware of sight – know that you are seeing. Rather than get entangled in what you see, just be aware of seeing…

Now be aware of sound – that hearing is happening. Let go of the interpretation of the sound and be aware that you can hear and are hearing…

Now be aware of awareness in a more general way. Perhaps you are aware of sights or sounds or temperature or sensations inside the body or many things at once. But also know that you are knowing. Be aware of awareness…

It’s miraculous. We can be aware! Notice if you can notice being aware…

Were you aware of seeing itself -- not the object but the actual seeing -- before I asked you? Probably not.

How much energy did you expend becoming aware of awareness? Pretty close to zero.

It does take effort to be aware of awareness – to remember to be aware of awareness. But it doesn't take much energy. That is the secret. Wise effort is very light and relaxed.

We haven’t answered the question, “How do we relieve suffering?” We haven’t even answered the question, “What is suffering?” other than to say it’s a kind of experience. But we have begun to answer the question, “What is experience?” When we look at our inner landscape, everything we experience falls into one of the five khandas.

I skipped lightly over the second khanda. It’s important and it’s been overlooked. So I’ll spend the next reflection on vedana. After doing that we’ll have a better map of our inner experience and can ask, “What turns experience into suffering?”

But before leaving the khandas in general, I want to suggest that the khandas themselves are important if for no other reason than to say, “Don’t confuse one kind of experience with another.”

For example, if you ask me what I’m feeling and I say I’m feeling like people don’t understand me, I have not actually told you what I feel. I’ve stated an interpretation of what other people might be doing (not understanding me), not how I feel about it (mad, sad, glad, scared, confused, or something else.) I’ve substituted a thought (sankhara) for a feeling tone (vedana). Thoughts are easy to see. Vedana is subtle.

Yogis often confuse one khanda for another, particularly confusing thoughts and ideas with other kinds of experience.

The Buddha said that if we can just know what’s going on inside, that’s enough to awaken us. If we know what’s going on, the mind knows what to do about it. But we have to know it on its own terms.

In the Satipatthana Sutta (MN 10) the Buddha says we must know feeling as feeling, perception as perception, thought as thought, delusion as delusion rather than substitute our thoughts for our feelings or labels for sensations.

In verse 34 he asks, “How does a person abide contemplating mind as mind?” Since our experience of mind is a field of awareness, the Buddha is asking, “How do we abide knowing awareness as awareness?” He goes on to answer his question:

“…He knows mind affected by lust as mind affected by lust, and mind unaffected by lust as mind unaffected by lust. He knows mind affected by hate as mind affected by hate, and mind unaffected by hate as mind unaffected by hate. He knows mind affected by delusion as mind affected by delusion, and mind unaffected by delusion as mind unaffected by delusion. He knows contracted mind as contracted mind and distracted mind as distracted mind. He knows exalted mind as exalted mind, and unexalted mind as unexalted mind. He knows surpassed mind as surpassed mind, and unsurpassed mind as unsurpassed mind … “ and so forth.

He advises knowing things on their own terms. This includes knowing awareness as awareness.

Awareness is a fundamental property of the universe. By “fundamental” I mean it cannot be split up into any sub-parts. We can break down an automobile or a flower into lots of constituent parts. But we can’t break awareness down into anything else. It is a fundamental.

And one of the mysterious properties of clear awareness is it soothes, quiets, and opens the mind-heart. We don’t have to do it. All we have to do is see things as they are — know delusion as delusion, hate as hate, kindness as kindness, and awareness as awareness.

Awareness of awareness is subtle, so along the way we may work with various objects to help the mind settle. But in the end, awareness of awareness is what’s most important.

Awareness of awareness can’t be forced. But it helps to recognize it as it emerges. We swim in a sea of awareness. Kabir wrote, “I laugh when I hear the fish in the sea are thirsty.”

If you can’t directly know the knowing right now, don’t worry. As awareness gets stronger, it will emerge all by itself. Just know that you don’t have to ignore it when it arises. We swim in it all the time.

Notes:

[1] “Samma Ditti Sutta: The Discourse on Wise View,” Majhima Nikaya 9:15.

[2] A number of the thoughts in this article were stimulated by a talk of his I heard in April, 2017.

Others in the Inner Landscape series:

1: Experience; 2: Vedana; 3: Dissolving Suffering; 4: Endearing; 5: Dependent Origination

Copyright 2018 by Doug Kraft

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use all or part of it for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the author. Specific licensing details are here.

How to cite this document

(a suggested style): "Inner Landscape 1: Experience" by Doug Kraft, www.dougkraft.com/?p=InnerLand1.