Chapter 2 from God(s) and Consciousness.

Other chapters: Introduction, 1. The Widening Circle, 3. Consciousness, 4. Is God Real?, and 5. Summary

I’ve worn glasses for forty-five years. I’m slightly farsighted and have a significant astigmatism in my left eye. Lenses compensate nicely. Looking through them, people, and the rest of the world come into clear focus.

But if you tried to look through my glasses, they’d probably make your vision worse. Each of us sees a little differently. What helps one person may give another person a headache.

This is the second talk in a series on God. By “God” I mean what is ultimately most real or ultimately most important in life.

We can directly experience ultimate reality. Many of us do, if only in moments. But we can’t adequately express it in words. Language is limited. Ultimate reality is limitless. The Chinese sage Lao Tsu wrote:

The Tao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Tao;

The name that can be named is not the eternal name. [1]

Christian mystics use the word “God” to name images and ideas about the ultimate. They use the word “Godhead” to point to the experience beyond images and ideas – the Tao that cannot be named.

In this series, we aren’t talking about the actual experience of ultimate reality. We’re talking about lenses that help bring that experience into focus. All of our minds and hearts have been distorted by our journeys through life. All of us are a bit nearsighted or farsighted or have some kind of astigmatism.

There are many lenses we can look through: God, Allah, Tao, Buddha nature, highest truth, nirvana, enlightenment, the Beloved, nature, the universe. The words and practices that help our mind-heart may be useless to someone else. And vice versa.

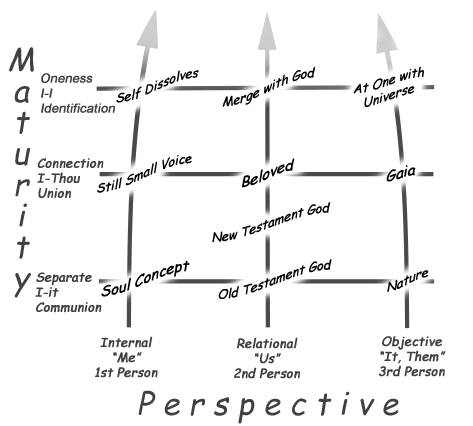

In the last talk we began to draw a map of all the lenses through which we might view what’s most real or most important in life. It has two dimensions: perspective and maturity.

We noted that perspective refers to where we look for God or Spirit. Some people look inside themselves: an internal view. Some look at how they relate to other people or things: a relational view. Some look “out there”: an objective view. Ken Wilber [2] calls these first, second and third person perspectives.

As we engage in any of these, it starts to unfold. So the second dimension on the map is maturity. Last time we looked at three developmental levels: separateness, connection, and Oneness or merging. Wilber refers to these as communion, union, and identification. The Jewish mystic Martin Buber might call them I-it, I-Thou and I-I.

Previously we looked in detail at the unfolding of the third person objective view of nature. Now we’ll look at God from relational and internal perspectives and some of the issues that come up around them.

In the West, the most familiar images of God are Biblical. These are relational perspectives with God as separate.

In Genesis, the first book of the Old Testament, we find two versions of this God. One is a remote and foreboding Almighty who moves across the face of chaos to divide light from dark, land from ocean, and day from night. Jehovah smites people and at least once destroys the world with a flood. The other Old Testament image of God is anthropomorphic: he walks in the Garden of Eden with Adam and Eve in early evenings. Both images are wholly other. We might communicate with Him. But He is very separate.

In the New Testament, Jesus’ God is more intimate. Jesus addresses God as “Abba,” an Aramaic word similar to “daddy” or even “dada.” Jesus’ relationship with God is suffused with parent-child love.

Politicians and TV evangelists would have us believe that most Americans subscribe to this view. But Gallop polls tell us that only a small minority (17%) believe in a traditional Biblical God.

Most reject this God as too literal and concrete. I’m reminded of Galileo’s inquisitioners. Church doctrine said nothing about moons around Jupiter, so they refused to look through his telescope. We wish they had.

The Biblical view of God is just a lens. Rather than critique it, why not take a peek? Why not suspend our skepticism and try to engage in a sincere conversation with the Ultimate and see what happens?

One of the easiest ways to relate to God is to sing to God.

I was introduced to Hindu and Sufi chanting back in the days when I was a hard-core scientific-materialistic atheist who had little patience with God language. Yet I loved to sing these simple songs the same way many of you love to sing Amazing Grace even if you don’t agree with the theology.

I invite you to indulge me and join in a devotional song. It uses the phrase “Lord of Light” to speak with a being “out there.”

Some of you will find it easy to give yourself to the singing. Some of you may hesitate. But don’t worry. You’ll be fine. It won’t cause permanent damage, I promise.

O take a hand, take a hand Lord of Light.

And make us whole again.

O take a hand my Lord of Light,

And make us whole again,

And make us whole again.

We humans are intensely relational creatures. We can’t survive without others. Relational instincts are deeply wired into us. Rather than fight them, these practices use them as a tool to bring us into a more intimate relationship with ultimate reality. If we engage these practices sincerely, our consciousness may gradually shift in several ways.

First, our hearts open. These are heart-centered practices. Devotion is not about what the mind thinks. It’s about what the heart feels. Our sense of love broadens and deepens. It becomes less sentimentally attached to a few particular people or things and more dispassionately embracing of all life.

With this, our sense of who or what we’re singing to or communicating with becomes more immediate. The 15th century ecstatic poet Kabir wrote, “I laugh when I hear the fish in the water is thirsty.” [3] God is an ocean and we’re inside it.

A Sufi chant sings “Ishk Allah ma bood leh la” or “God is the lover, the beloved and love itself.” The distinction between us and Abba, between us and ultimacy, begins to come together in union.

If we carry these practices with us all the time, the sense of who or what is singing or praying starts to thin out. Rumi wrote: “It is said that love comes through a window in the heart, but if there are no walls, there's no need to have a window.” This is merging with the Light, becoming One with the unnamable All.

We’ve risen from separateness through connection to merging. It’s not an intellectual thing but a heartful movement from communion to union to identification.

Right before we disappear off the top of the map into the direct experience of the Tao or the Godhead, there’s still a wisp of lover and beloved. But it’s not the same God or Spirit of Life found in the younger levels.

Now, turning from the relational perspective to the first person internal perspective, we find a similar movement. However, this perspective emphasizes the mind rather than the heart, what we see more than what we feel.

Imagine a person coming across a book describing the God within: the inner light, Atman, soul essence. “What a great idea,” she thinks. “I like the thought of a divine essence in me.”

This is an internal separate view. It’s internal because it’s inside her and it’s separate because, despite her enthusiasm, it’s just an idea, not an experience.

Nevertheless, it may be enough to get her to examine her deep experience. Maybe she takes up meditation. She senses stirrings within she hadn’t noticed before – subtle but tangible.

She’s rising from separateness to connection, from communion to union. Kabir sometimes wrote with the voice of a first person union God:

… You will not find me in stupas, not in Indian shrine rooms, nor in synagogues, nor in cathedrals:

not in masses, nor kirtans, not in legs winding around your own neck, nor in eating nothing but vegetables.

When you really look for me, you will see me instantly

you will find me in the tiniest house of time.

Kabir says: Student, tell me, what is God?

He is the breath inside the breath. [4]

“The breath inside the breath,” is an internal, connected view. One time Kabir put it more simply: “The God whom I love is inside.” Quakers refer to this as “the still small voice within.”

If she continues to explore this still small place within, it may not seem so small. The clarity, peace, and love inside grow stronger until she, the observer, begins to dissolve into this inner quiet.

Kabir writes, “Because someone has made up the word ‘wave,’ do I have to distinguish it from water?”

The merging of the wave with the ocean is similar in all three perspectives, but has slightly different flavors.

From the third person objective perspective we see the immensity of the ocean of existence. We’re a tiny, single wave. But we’re part of it all nonetheless. We’re at One with the universe.

From the second person relational perspective, the ocean is vast but our relationship with it feels more intimate and personal. We merge with God.

From the first person internal perspective, we know we’re a wave, but our essence is the same as the ocean. As our awareness moves from the shape of our wave to the ocean, our self-sense dissolves.

All three ultimately point to the same experience. Yet because of the limitations of language, anything we say has the flavor of one of the three perspectives.

“At One with the universe,” “merging with God,” “self dissolving” are just lenses. Ultimate experience is beyond perspective and beyond language. The Tao that can be spoken isn’t the true Tao.

If we step back from all these levels and perspectives and look at the whole map, we notice that religion in the West got a little stuck on the relational separate view. I’d like to put this into a historical context and hint at the implications it has for the human condition in the twenty-first century.

Remember, these three perspectives are different realms of human experience. As noted in the last talk, art is the internal realm: how something touches us inside. Art is in the eye (or “I”) of the beholder. Morals and ethics are in the relational realm: how we treat one another. And science is in the objective realm – a scientist takes an impersonal external view.

Through the late medieval period, arts, ethics, and science were fused: they weren’t well differentiated. Art was restricted to religious themes. Morality was based on Biblical injunctions. Scientific findings had to be reconciled with church doctrine or be rejected.

The Western Enlightenment began about 400 years ago in the time of Galileo. Its great accomplishment was the separation of these three realms so each had its own dignity and could stand on its own apart from the church. [5]

Artists began to paint non-religious themes: landscapes, still-lifes and everyday scenes. Philosophers began to think about ethics outside the confines of church teaching – they called it “natural philosophy.” Scientific discoveries were seen as legitimate whether the church approved or not.

Freed from the yoke of the church, science took off. It made staggering advances in astronomy, physics, medicine, food production, transportation, communication, technologies and on and on. It extended life expectancy by several decades.

Science was so successful that it began to dominate the way people thought. Its third person objective perspective became more than just A way to view life. It became THE way. Objectivity was in. Internal and relational views were passé.

As one philosopher put it, before the Western Enlightenment, to be caught on your knees praying was a sign of maturity, dignity, and wisdom. After the Enlightenment era, to be caught on your knees praying was an embarrassment and sign that you were quaint, old fashioned and out of touch with modern sensibilities.

While the Enlightenment’s scientific achievements improved the human condition in many ways, in other ways it was a disaster.

Science knows little about values. Morals and values come from the relational realm. Science gets its strength from being objective and value-free. Science can tell us a great deal about the difference between a pine tree, spotted owl, yellow-tailed butterfly, and comet. But it can’t tell us which is better or worse, more valuable or less valuable. Instinctively, we know love is better than hate and generosity is better than selfishness. But science shows us nothing of these.

Meanwhile, the traditional church remained stuck in a relational perspective, and a relatively young level.

Karen Armstrong, a popularizer of Biblical scholarship, noted that most people first learn about God around the same time they first learn about Santa Claus. [6] After all, both are bearded gentlemen with loving and kind intentions.

This lens on God isn’t bad or wrong. It portrays a loving, welcoming universe. It encourages kindness and thoughtfulness. It’s appropriate for the concrete, literal thinking of a child. But for the nuanced complexities of an inquisitive adult mind, it’s a little goofy.

So our view of Santa Claus evolves as we grow. Unfortunately, for many people the word “God” remains stunted in a mythic consciousness appropriate for a seven year old.

There are many exceptions to this. Many people have matured beyond this.

Still, if we meet a stranger on the commuter train and he uses the word “God,” our first assumption may be that he was talking about an infinitely perfect Santa Claus. This is too bad.

As I noted earlier, only 17% of Americans actually subscribe to a literal Biblical God. Most have more rational, pluralistic, and connected ways of thinking.

However when it comes to public discourse on religion or values, the West is developmentally arrested. We don’t have a shared vocabulary, set of tools, or institutional support for these discussions because they can’t be couched in objective scientific thinking and popular religion remains mired in young relational ways of thinking.

Unitarianism is one of the many exceptions to the general trend. For four hundred years we’ve insisted on pluralistic thinking, inclusion, diversity, and seeing things from multiple perspectives. Our banners around the sanctuary and symbols in other Unitarian Universalist congregations declare that there are many valuable lenses through which to view ultimacy.

Nevertheless, we have our quirks. Many feel betrayed by the limitations of the traditional church. Sometimes we throw out the baby with the bathwater. In rejecting those limitations, we sometimes reject the entire second person perspective as a legitimate place from which to grow and evolve. Some of us are wary of God language.

Next time I want to pick up here and look at where we are today. There is a level of consciousness that has matured beyond separateness but hasn’t fully found connection. It connects with some people but not all people. It identifies strongly with one group, religious brand, ethnicity, or nation and treats others as unworthy of care or concern. It accepts one set of values passed down from some higher source and treats others as a threat.

This consciousness breeds most of the world’s terrorism. It’s the source of take-no-prisoners politics and “I know how to run the country and anyone who disagrees is in the way.” It arguably contributed to our economic recent melt down ago as well as to the assault on public education, health care, environmental sensitivity and so forth.

If we want to be a force for healing in the world, we need to address more than just individual issues. We must help this consciousness mature.

To be spiritually literate, we must be fluent in all perspectives and all levels without confusing them. To enrich our lives and be in meaningful dialog with the world, we need to be able to converse clearly and compassionately in all perspectives and at all levels. And we need to encourage ourselves and others to mature toward higher levels rather than defend where we or they are now.

If we can find ourselves on the map of consciousness, we still have more to grow. The Tao that can be thought is not the true Tao. Any concept of God is just a lens, not ultimate reality. Any view that isn’t imbued with our ultimate potential misses some internal beauty, relational goodness or objective clarity.

_____________

Notes:

1. Translation by Ren Jiyu et al. (1993)

2. Ken Wilber, Integral Spirituality, (Integral Books: Boston and London), 2007. One Two Three of God, audio recording by Sounds True, www.soundstrue.come.

3. Robert Bly, The Kabir Book: Forty-Four of the Ecstatic Poems of Kabir , (Beacon Press, Boston, 1977), p. 9

4. Robert Bly, op. cit. p. 33

5. Ken Wilber, The Marriage of Sense and Soul, (Random House, New York, 1998)

6. Karen Armstrong, The Case for God, (Alfred A. Knof, New York, 2009), p 320.

Copyright 2012 by Doug Kraft

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use all or part of it for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the author. Specific licensing details are here.

How to cite this document

(a suggested style): "2. Spiritual Literacy" by Doug Kraft, www.dougkraft.com/?p=Gods2Literacy.

Read more:

doug, April 12, 2020

Test