Click here for a pdf of this reflection. Other reflections in the Inner Landscape series are:

1: Experience; 2: Vedana; 3: Dissolving Suffering; 4: Endearing; 5: Dependent Origination

In the last two reflections in this series we’re going into the belly of the beast – into the core of the Buddha’s teaching. It’s called “Dependent Origination” or “paticcasamuppada.” The Buddha said, “One who sees Dependent Origination sees the Dhamma [or the whole of his teaching]; one who sees the Dhamma sees Dependent Origination."[1]

Dependent Origination means, “Everything is dependent on something else for its origination.” Or more simply, “Everything has a cause. That cause has a cause. The cause of that cause has a cause. And so on.”

Dependent Origination is a string of causal relationships. Picture a line of dominos. One falls knocking over the next one, which knocks over the next and so on down the line. In Dependent Origination, the first domino is so tiny we may not notice it. Each successive domino is a little larger. The last one is the whole catastrophe: pain, anguish, grief, despair, and bummers of all varieties.

Nature has many such causal chains that interact in a matrix in which everything directly or indirectly affects everything else.

The Buddha was most interested in the causal forces that result in dukkha or suffering of any variety. So he reverse engineered his own suffering. He carefully analyzed how it works. He saw that experience of suffering was preceded by some kind of action. It might have been as obvious as physical or verbal action or as subtle as mental action, resistance, or identification.

These actions and identifications were preceded by habitual tendencies out of which the actions arose. These habit patterns, in turn, had been stimulated by a thought. That thought had been preceded by a pre-verbal liking, disliking, or confusion. And so on.

He reverse engineered the processes leading to his own suffering and dissatisfaction. That showed him how suffering arose. Usually we reverse engineer a widget so we can produce our own widget. But the Buddha was not interested in teaching us how to produce misery. We’re pretty good at that already.

He wanted to understand how bummers arose so he could stop them. He wanted to know how to keep one of those dominos from falling over; or how to take one out of the line; or how to spread them far enough apart that one might fall without knocking over the next. If he understood paticcasamuppada enough, he might be able to shut the sequence down.

And he did. It worked. He woke up and became fully liberated.

The Buddha solved his problem. But that doesn’t solve ours. We have to reverse engineer our own angst and dissatisfaction.

We have to do this ourselves because suffering is internal. There can be external events in the causal chain. But the suffering at the end of the line is subjective. The Buddha’s descriptions are only approximations. They may not match our experience exactly.

To solve our problem, we have to understand our angst and dissatisfaction in more detail than anyone can convey to us. If we look openly, deeply, kindly, and directly inside, all we need to know is right there. But we can only come to know it intimately by observing our own process.

To unplug our suffering, we have to reverse engineer it enough to understand that causal chain of events.

To sort out the causal chain, there are two things we should bear in mind:

(1) Causation is not always linear. Some causes line up single file. Others split into multiple lines, converge from multiple lines, or run around in circles of causes and effects. That’s natural.

(2) More importantly, we must distinguish between triggers and causes. The Buddha distinguished between a precipitating trigger that sparks an event and its root cause. The trigger can be removed and the suffering continues. But if the root is removed, the suffering stops.

Ananda once asked the Buddha:

Venerable sir, in what way can a monk be called skilled in dependent origination?

The Buddha responded.

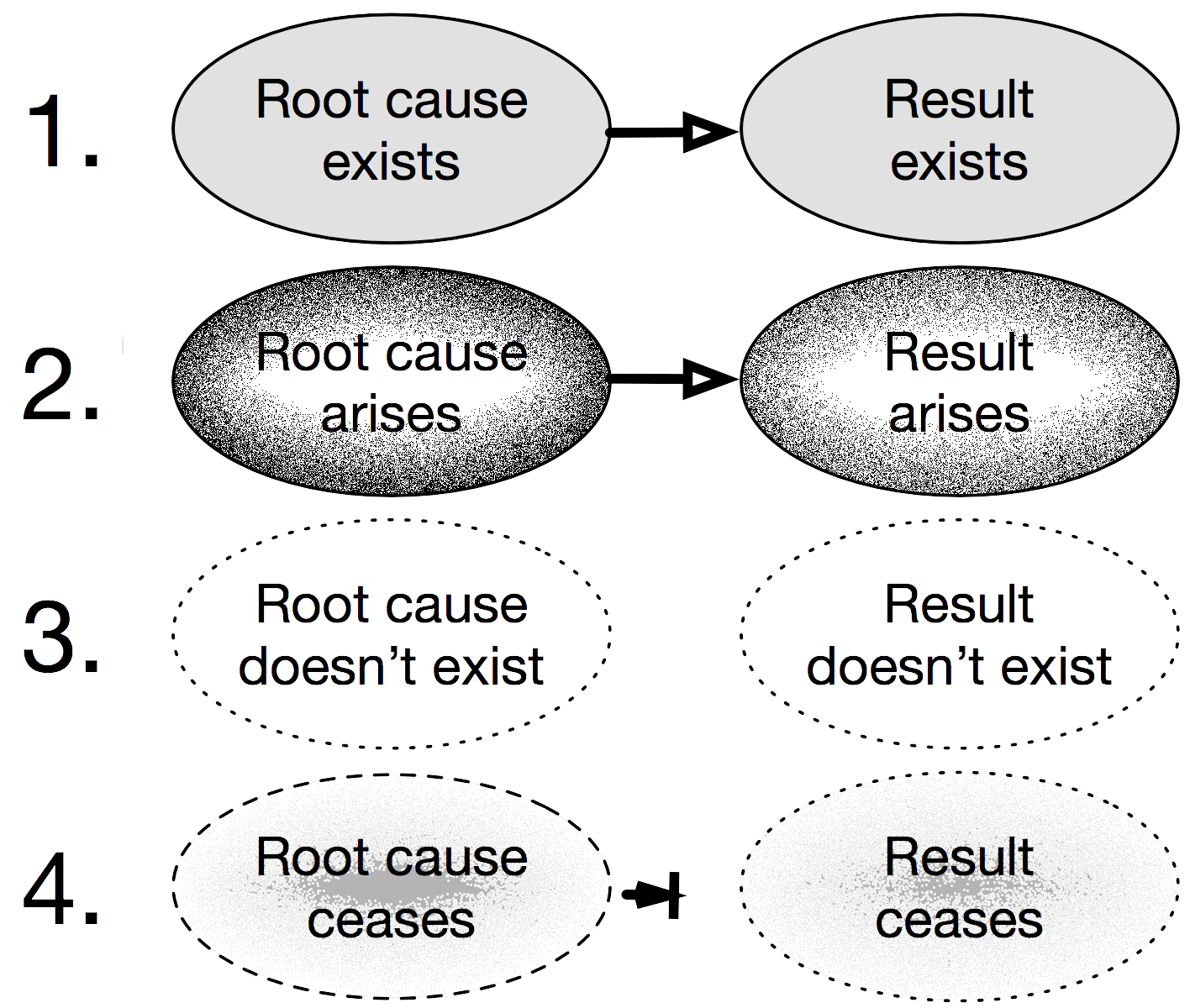

When this exists, that comes to be; with the arising of this, that arises. When this does not exist, that does not come to be; with the cessation of this, that ceases. [2]

He described four relationships between a root cause and a resulting effect. They could be diagramed as follows:

The fourth relationship is the one that is most important for ending suffering. For example:

If I throw a match into a dry field (action 2), it sparks a brush fire. If I remove the match (action 4), the fire continues. From the Buddha’s perspective, the match is a precipitating trigger, not a root cause. The root cause is dry grass. If it is not present (condition 3), there’s no fire. If there is a fire and the grass is removed or turned into wet grass (action 4), the fire ceases.

To really alleviate suffering, we have to remove the root causes (action 4).

Closer to home, consider what happens when someone makes a snide remark. If I find it irritating, I may blame my irritation on the other person or try to only be around nice people. However, the root cause of the irritation is not other people. It is the irritability in me that can be triggered by the comment. Without the irritability, there is no irritation.

So if I want to eliminate the suffering of irritation, I must figure out how to relax my underlying irritability.

Here’s a different kind of example in which positive qualities arise because of causes and conditions:

A man came to me with cancer. The doctors gave him a 50-50 chance of surviving – a sobering diagnosis. He wanted help in dealing with his mortality as well as navigating the rich layers of emotions his prognosis brought up.

I had known him casually for many years. The fact that he was asking for help was out of character. Since the diagnosis, his personality had shifted in other ways. He was more loving with his family and friends. His self-centeredness had evaporated. He had a peaceful clarity about what was essential and unessential in life.

As we talked, it was clear to both of us that his wisdom, compassion, and wellbeing were dependently arisen. They were dependent on death breathing down his neck.

I encouraged him to look deeply into these wholesome qualities while they were present and find practices to support them. Otherwise, if his cancer went into remission, he might lose them.

He didn’t practice. He rode the peace and wellbeing without exploring them. His cancer did go into remission. In several years he was pronounced cured.

We rejoiced. And he slipped back into his old slightly narcissistic, shallow personality. The wisdom and wellbeing faded. His old habits reasserted themselves and he reverted to a more painful way of relating to family, friends, and life.

Peace and wellbeing, like everything else in the relative world, arises because of causes and conditions. They aren’t permanent. For him, a root cause was death in his face. When that ceased for the time being, peace and wellbeing ceased. Without another root cause, he reverted to his old personality.

If we want peace in our meditation practice, we can generate it with intense, one-pointed concentration. Then our peace will depend on being in intense one-pointed concentration.

If we want peace in other parts of our lives, we need a cause that can stay with us when we aren’t on retreat or meditating with our eyes closed to the world.

What the Buddha meant by “cause” is a little different than the word implies in English. The Buddha was not interested in what triggered suffering. He was interested in the root cause that, if removed, caused the suffering to fade.

It’s helpful to reflect on the root causes of the qualities we value in our lives. When we cultivate the root circumstances, we are acting with wisdom.

We all have to reverse engineer our own experience because it’s a little different for each of us. However, we are all human. There are general patterns in Dependent Origination that we all share. Understanding the pattern helps us discover our unique expression of it.

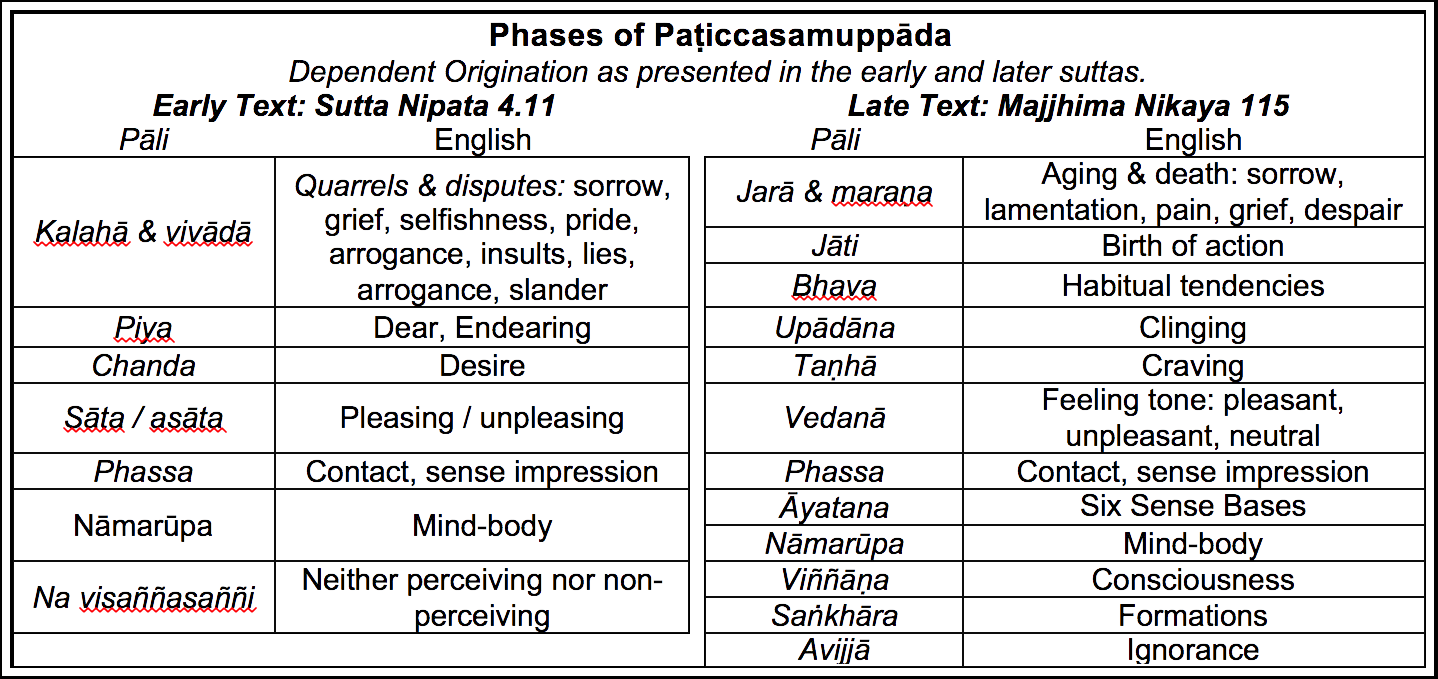

Perhaps the most widely known version is called “The Twelve Links of Dependent Origination.” We find it scattered through the Majjhima Nikaya, the Samyutta Nikaya, and other collections of suttas. It is summarized on the right side of the table on the next page.

It was first recorded two or three centuries after the Buddha. Prior to being transcribed, it had been passed down orally from monk to monk for generations. During this transmission, it was codified to make it easier to memorize. The same codification can make it mind numbing to follow.

So I’ll describe a different version that is shown on the left side of the table. It comes from an earlier collection of suttas called the Atthaka Vagga. This collection of 16 talks may be the oldest record we have of the Buddha’s teachings. It was probably written down during his lifetime and comes closest to what he actually said.

In these suttas the Buddha is not referred to as “Lord Buddha” or “The Blessed One.” He’s simply “the wanderer,” or “Sir Gautama.” It’s early in his ministry. There is no sangha yet – it would gather as the years passed. Still, he’s charismatic and deeply respected as he struggles to find words to express his extraordinary experience. In these suttas there is no eight-fold path, four noble truths, five hindrances, three characteristics, twelve links, or numbered anything. There’s just informal dialog.

The eleventh sutta of the Atthaka Vagga (found in Sutta Nipata 4.11) contains what scholars consider the earliest record of Dependent Origination. He doesn’t even use the term “paticcasamuppada.” Nevertheless he lays out a string of causal relationships in response to a series of questions. The sutta begins with a question posed to the Buddha:

Where do disputes and quarrels (kalaha vivad0 come from? And sorrow, grief, and selfishness? And the pride, arrogance, insults, and lies that come with them? Why do they happen? Please tell me.

Notice that dukkha (suffering) is described as quarrels and disputes, rather than birth, aging, sickness, death, etc. in the later versions. It’s the same idea but the images are closer to everyday life.

The Buddha answers:

Disputes and quarrels come from what we hold dear (piya). Sorrow, grief, and selfishness, pride, arrogance, and slander come with them. When we argue we speak spitefully. Selfishness is yoked to quarrels and disputes.

He says dukkha comes from what we hold dear (piya). In the later suttas it’s called clinging (upadana). It’s the same idea, but the language in the early text is less accusatory. We hold our children dear and they do cause us suffering. But we wouldn’t trade them in or fault ourselves for endearing them. However, we might fault ourselves for clinging. In using “endearing,” the Buddha wasn’t passing moral judgment. He was just describing how it works.

The questioner asks:

Where does endearing (piyasu) come from? Why do we feel the longing and greed that go with it? What creates hopes and aspirations?

The Buddha responds:

Endearing comes from desire (chanda) – we want things. Greed is part of the worldly life. It causes hopes and aspirations for the future.

Endearing comes from desire or longing (chanda). In the later texts it’s called craving (tanha). It’s the same idea, but less moralistic in the early version. Again, the Buddha is not judging, just describing what happens.

Question:

Where does desire (chanda) come from? And what about preferences, anger, lies, doubt, and all the states the Wanderer talks about?

The wandering Buddha responds:

Desire (chanda) comes from what we call “pleasing” and “displeasing” (satam asatanti). Likewise, when people see how things come and go, they form preferences accordingly.

Anger, lies, doubt, and confusion follow. We’re bound by the duality of pleasing and unpleasing. If you doubt this, train yourself to know it. You’ll understand when you’ve seen what these states are like.

The words pleasing and unpleasing (satam asatanti) become feeling tone (vedana) in the later suttas. Vedana means pleasant, painful, or neutral. It’s the same idea.

Question:

Where does the feeling of pleasing or unpleasing come from? When are these states absent? What makes them come and go? Please tell me.

The Buddha:

Pleasing and unpleasing come from sense impression (phassa). Without sense impressions, they don’t occur. The same happens with coming and going – they come from sense impressions.

The word for sense impressions is “phassa.“ Phassa is often translated as “contact.” It means raw sensation without interpretation.

Question:

So where in this world do sense impressions come from? Why do we grasp things? What must be absent for this selfishness to fade? What needs to be gone, for sense impressions to disappear?

The Buddha:

Body-mind depends upon sense impressions. Grasping things comes from calling them “mine.” When there is no desire, there is no sense of self. When body-mind is gone, there are no sense impressions.

In other words, if you want to get rid of sense impressions and the selfishness and desire that come with them, get rid of the body-mind. That’s probably not going to happen! A nicer way to say this is that the tendency toward grasping and a sense of self arise out of body-mind itself. The forces of evolution favored those who had a fierce instinct to protect the integrity of the body. Those who were lackadaisical about keeping the body going were eaten and taken out of the gene pool. There is no self that creates this instinct any more than a self that causes the knee jerk reflect. It’s a by-product of our genetic inheritance. It just emerges from natural body-mind processes.

Question:

What do we have to do for sense impressions to disappear? For happiness and unhappiness to cease? Tell us please, we really want to know.

The Buddha:

Neither perceiving, misperceiving, nor non-perceiving – in this state, mind-body vanish from awareness. Conceptualizing is where the problem starts. Conceptualizing is also the cause of obsessive thinking.

Perception involves conceptualization, if only to put a label on an experience. As the mind gets deeply relaxed, conceptualizing stops.

Remember in dependent origination, the dominos get smaller and subtler as we move up the causal chain. The Buddha describes a state where there is neither perception, misperception, nor non-perception. It is indeed very subtle. But as you go up the jhanas, you will experience it.

Question:

Whatever we have asked, you’ve revealed to us. Another question, please. Do all the wise men say this is the highest purity? Or is there something higher?

In other words, is neither perception nor non-perception the highest we can attain? The Buddha answers:

Some wise men say this is the highest. And some speak of a state where nothing remains. A genuine sage knows how everything is conditioned. Understanding conditioning, he is free and content. Knowing better, he does not dispute. The wise do not keep becoming.

”Not becoming” means enlightenment.

The implication is there is nothing but a stream of conditioned phenomena that flow on and on. There is no self-essence behind it, just changing experience. There is no self, just fluctuating phenomenon. When we fully understand that, we are free. Phenomena flow on, but there’s no longer the sense of an independent self caught in the chain of events. If there is no one to suffer, there is no suffering.

Notice this is not a theological, philosophical, or metaphysical claim. It is just an experience. Hence there is nothing to dispute.

The sutta ends by returning to the original question about quarrels and disputes. The wise don’t engage in them.

Leigh Brasington is a scholar with a mature meditation practice. He comments on this sutta:

These verses, rather than feeling like the record of an actual conversation, have the feeling of being intentionally composed – the questions are just too perfect, with each set of questions having a single answer. But this does not detract at all from the significance of this sutta – it is clearly a well thought out discourse describing a series of "necessary conditions." This is the links of Dependent Origination in their earliest form. It would seem that any explanation of links of Dependent Origination ought to harmonize with this early description if the later description is going to be accurate. This is as close as we can get to the Gold Standard for understanding the Buddha's original thinking about Dependent Origination. And given what the Buddha says …, understanding his early thinking on Dependent Origination is a requirement for awakening. [3]

So in the last two reflections in this series, I’d like to unpack the various aspects of Dependent Origination, describe how they manifest in meditation, and offer ways to work with them in our practices and lives.

I’ll close this reflection by coming back to the punch line of Dependent Origination. Indeed, it can feel like a punch in the stomach. The Buddha says our suffering arises out of endearing — out of holding onto what we find most precious and valuable in life.

The Udana (8.8) tells a story about Visakha who comes to the Buddha with wet hair and wet garments. The Buddha asks her what this is about. She says her granddaughter died and she is beside herself with grief.

Visakha has many children and grandchildren. So the Buddha asks if she would like to have as many descendants as there are human beings in Savatthi, the small city India where she lives.

She says she’d like that very much.

The Buddha asks how many humans die every day in Savatthi. She says “many.”

The Buddha replies that her daughter is not unusual. People die everyday. It’s natural. If she had as many children as there were people in the city, she’d be grieving all the time. The Buddha concludes:

Whatsoever grieves or lamentations or sorrows

Are in the world, of whatsoever sort or kind,

Arise because of something that is held dear.

If nothing is held dear, these don’t arise.

In this poignant teaching moment the Buddha impresses on her the cause and effect relationship between what she holds dear and suffering.

This resonates with Taoist teachings about the connection between sunlight and shadows, joy and grief, love and pain.

But I don’t think the Buddha is recommending ridding ourselves of loved ones or closing our hearts. His point is the opposite. He’s recommending that we love mightily but not get hooked; open our hearts to the world but remember that everything we love will vanish. He recommends dispassion but not disinterest.

We cannot draw up dispassion through force of will. It cannot be done with stern resolve. It can only be cultivated by softening and opening as we look with clear eyes at how the world truly is.

The Buddha is encouraging us to mature beyond our evolutionary tendencies toward defending or running away – fight or flight. He’s encouraging us to stay steadfastly with things as they truly are.

There’s another an ancient story about this. I don’t remember the tradition it comes from, but it speaks to the Buddha’s point.

Once there was a teacher-rabbi-priest-guru-saint of great wisdom. A student came to him mourning the lost of a dear friend. The student asked, “How can I find peace in this life knowing that everything I hold dear will be taken from me?”

The teacher smiled in a comforting way. Then he lifted a glass and said, “This lovely goblet was given to me by a dear student of mine. I can hold it up and lovely patterns of sunlight flow through it. It is beautiful.

“But I know this glass is already broken. It’s just a matter of time. I know this deep in my heart.

“You don’t accept this. So you try to protect the glass, lock it up safely in a cupboard where you can’t enjoy it. For you it becomes an object of fear and protection.

“But it doesn’t matter. Someday the cat may knock it off the shelf or some other accident will happen. It is inevitable.

“So rather than try to escape what is impossible to avoid, I enjoy it while it’s here. I savor it because my time with it is precious and fleeting.

“And when it does breaks, I’ll say ‘Of course.’”

“When you train yourself to know that everything is already broken, rather than shrink into the shadows, your heart opens widely.”

I close with some questions for reflection:

1. What do you hold most dear? What people, ideas, things, values are important to you?

2. How do you hold what is most dear? Do you love because you want something back? Do you care because you want care in return? Are you kind in order to make people kinder to you? Is this a kind of bargaining like a monetary exchange? A means to an end? Or are love, care, and kindness ends in and of themselves?

When we see that the glass is already broken, that all relationships will end some day, then we stay open just for the sake of love, caring, and kindness. Then we are free. At first, freedom may have a bittersweet poignancy. But it is the path to true liberation, bound by nothing, eyes clear, and heart open to the winds of change.

Lao Tsu wrote:

Desires wither the heart.

The Master observes the world

but trusts his inner vision.

He allows things to come and go.

His heart is open as the sky.[4]

Notes:

[1] The Greater Discourse on the Simile of the “Elephant's Footprint: Mahahatthipadopama Sutta ” Majjhima Nikaya 28:28

[2] “Bahudhatuka Sutta: The Many Kinds of Elements,” (Majjhima Nikaya, 115:11)

[3] http://www.leighb.com

[4] Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching. Translated by Stephen Mitchell. (Frances Lincoln Ltd: London. 1999.) verse 12.

Others in the Inner Landscape series:

1: Experience; 2: Vedana; 3: Dissolving Suffering; 4: Endearing; 5: Dependent Origination

Copyright 2018 by Doug Kraft

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use all or part of it for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the author. Specific licensing details are here.

How to cite this document

(a suggested style): "Inner Landscape 4: Endearing" by Doug Kraft, www.dougkraft.com/?p=InnerLand4.