Chapter 13 of Meditator’s Field Guide copyright 2017, Doug Kraft.

The way is not in the sky. The way is in the heart.

If we’d like to get our selves out of the way, deepen our meditation, or bring more clarity and vitality into our lives, relating skillfully to vedana is very helpful. However, it isn’t always obvious what vedana is, much less how to relate to it wisely.

Vedana is a Pali term usually translated as “feeling” or “feeling tone.” It is not emotion. Emotions are complex. Vedana is simple, although it is one ingredient of emotion. Vedana is the level of pleasantness or unpleasantness in any experience. That’s all. It is modest, subtle, and often difficult to recognize in the clamor of thoughts and emotions. But with a little practice, we can get to know it well.

I first stumbled into its importance many years ago, though it took me decades to appreciate what I’d found. So I’ll begin with that story. Then I’ll unpack what vedana is and its central role in the Buddha’s teachings followed by a tool that helps us relate to it wisely. I’ll also show how that tool can relate to other essential qualities of awareness.

First the story:

During my first year of college, my high school girlfriend jilted me. I understood her reasons, and still felt brokenhearted. As the sting subsided over several months, I began corresponding with a close friend. I wondered if something more was possible between us. As Spring break approached, I offered to take a six-hour bus ride up to New England and visit her at her college.

When I finally saw her, she said, “What are you doing here? I couldn’t figure out why you were coming.”

“Oops,” I thought, “I misread this.” My insides knotted in embarrassment. I wanted to run. But the bus home didn’t leave until the following day. Awkward!

The next morning I gazed out the bus window as it rolled south. The melting snow revealed dirt and grime. The woods were leafless and gray. A melancholic fog shrouded the countryside. Nature mirrored my mood.

I began writing song lyrics about gray skies and tarnished snow. After a while I noticed I was feeling better. This surprised me. Writing helped me see my life with a little dispassion. The loneliness didn’t abate. But my mood seemed manageable. I knew it would pass and I’d go on to live another day.

I thought, “What a wonderful tool! If I can express what’s really going on inside, it takes the edge off.”

The tool required stepping back from my emotions. But I wasn’t pushing them away — quite the opposite. I was stepping back to see them clearly in a larger context. The feeling tones were fuzzy, so exact words weren’t possible. Yet images and metaphors gave satisfying hints. That was enough.

What a lovely tool!

I had stumbled into something like the Six Rs (see "Three Essential Practices ). I didn’t have that nomenclature or all six elements. But I had the essence of turning toward, relaxing into, and savoring whatever came up (see). This strange combination worked.

Recently I learned the neural physiology underpinning this phenomenon. The circuits that register raw pain and pleasure feed into the lower brain — the reptile cortex. There is no self-awareness in that region. Self-reflection arises in the higher brain — the neocortex.

The neocortex is home for labeling, conscious thought, ideas, poetry, stories, and concepts. However, the neocortex doesn’t directly receive signals of pain and pleasure. Therefore, pleasantness and unpleasantness are preverbal and precognitive. They can fly below the radar screen of conscious awareness until signals are relayed to higher centers. And not all signals are sent “upstairs.”

While I was composing lyrics, the locus of brain activity shifted to the neocortex, which doesn’t register pain directly. This put some neural distance, if you will, between those difficult feelings and my reflections.

Many of us understand this instinctively. In rough times, we may look for mental distractions or intellectually analyze our situation. This creates some neural distance. However, ignoring physical or emotional stress has long-term problems. Denial doesn’t allow us to integrate the difficulty or respond compassionately. The stress in the lower brain becomes a guerrilla cadre that roams around undetected as it looks for things to blow up. We may think we’re fine until something triggers an outburst.

The trick is to engage the higher brain’s wisdom and understanding without ignoring data in the more primitive, pain-receptive areas. Writing lyrics that reflected what I was feeling did that for me. Even if the poetry was bad, the intention to understand and express was sufficient.

This is a middle path between getting lost in the raw stress of the lower brain and getting lost in the stories, concepts, and analysis of the higher centers. At the very least, we have to learn to tolerate difficult states long enough to see them clearly as they are.

The best tool I know for doing this is the six Rs: Recognize what’s going on in its own terms; Release it or let it be as it is without trying to control it; Relax tension, Re-Smile or bring lighter states into the mix; Return to our base practice; and Repeat as often as needed.

The Buddha did not know neural physiology. That information wasn’t available 2600 years ago. But he understood the phenomena itself with remarkable clarity. And he had a word for the result: equanimity (upekkha).

Equanimity is not being oblivious to the delight and bummers that flow through our lives. It is seeing them so openly that they don’t throw us off balance. With equanimity we know what’s going on, but understand the larger, deeper, impersonal nature of life itself.

When equanimity is strong, the mind-heart becomes steady enough to see pleasantness and unpleasantness without immediately having to do something about it. We can see pleasantness as pleasantness without grabbing it or holding on. On the painful end of the scale, I could sit on the bus and see my inner states without trying to change them. I was more interested in describing them than in fixing them. Though I didn’t know the word “vedana” at that time, the writing process helped me peacefully watch the textures of pleasantness and unpleasantness as they ebbed and flowed.

Getting our selves out of the way is the theme of this section of this field guide. Observing vedana with equanimity is key to seeing how the sense of self arises and gets in the way in the first place.

If vedana is pleasant, the mind tends to move toward the pleasant feeling tone. If the vedana is unpleasant, the mind tends to move away. This leaning towards or away creates a sense of someone — a self — moving toward or away from something — an object. Wanting and not wanting are different flavors of “craving” (tanha). In this case, rather than just an impersonal flow of phenomena, experience begins to split into self and other.

However, if the vedana is relaxed, it can dissolve and a sense of self does not congeal out of the flow of phenomena.

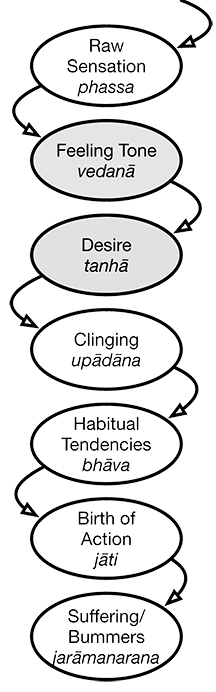

Vedana appears in many other teachings of the Buddha. It is the seventh aspect of Dependent Origination (paticcasamuppada) where raw sensory experience (phassa) can give rise to feeling tone (vedana) and feeling tone can tighten into craving (tanha).

Vedana is also the second of the five aggregates (khandas or clusters of experience) and the second of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness. In fact it is mentioned throughout the Buddha’s discourses.

However, other than implying that vedana is very important, the Buddha says little about it. For example, the “Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness” (“Satipatthana Sutta,” Majjhima Nikaya, 10), describes the other three foundations — body, mind, and dhammas — in detail over many pages. Meanwhile, the second foundation, vedana, receives one short paragraph.

In the classical commentaries on the Buddha’s teachings, vedana is mentioned often but usually without commentary. In contemporary Buddhist writings, there is little exploration of vedana.

Perhaps because vedana is subtle, preverbal, and preconceptual, it is hard to find words or concepts that are helpful. We’re left to work it out for ourselves by exploring our own experience.

One of my teachers, Tony Bernard, came up with an elegant strategy for exploring vedana. He calls the strategy a “mental app” which he named “The Vedana Meter.” Rather than installing the app on your smart phone, you install it in your mind. This is how it works:

You walk into the doctor’s office and say, “I have this soreness in my right arm.” The doctor asks, “On a scale from zero to ten where zero is pain-free and ten is excruciating, how intense is the pain?”

After a moment’s reflection, it’s easy to give numbers: “In the morning, it’s usually a two. In the evening it’s a six. Right now it’s four and a half.” Those numbers are measures of unpleasant vedana.

We could also set up a pleasantness scale: “On a scale from zero to ten where zero is boring and ten is total delight, how is eating that cookie?” “… petting a kitten?” “… spring flowers?” “… your favorite music?”

A complete vedana meter has both scales. It runs from the worst intensity you could experience without blacking out to the loveliest rush you could know without blissing out.

To create your vedana meter, imagine such a scale in your mind. You can design it any way you like.

Tony’s looks like a circular car speedometer. Zero on the left is the most painful. Ten on the right is the most wonderful. Five in the middle is neutral.

The first image in my mind was a horizontal bar that ran from -10 on the left (torture) to 0 in the middle (neutral) to +10 on the right (bliss). A needle moved back and forth on this scale.

As I used the scale, the needle vanished and two shaded bars appeared. Each started in the neutral middle and grew outward in one direction or the other depending on how pleasant or unpleasant an experience was. Sometimes both bars grew in opposite directions at the same time. Some experiences were pleasant and unpleasant all at once.

Another yogi’s vedana meter resembled a stereo equalizer with different scales for different frequencies.

The mental images are just metaphors. So use whatever works most naturally for you.

Once your vedana meter app is complete, you can calibrate it. To do this, bring to mind a range of pleasant and unpleasant experiences and see how your meter responds. Remember, what’s important is not what you think about the phenomenon but how pleasant or unpleasant it feels.

For example, see how your meter registers the following:

Once you’re familiar with how your meter responds to a wide variety of experiences, you’re ready to bring it into meditation and life:

• What does the meter register at this moment?

When I first tried out my app, it seemed pretty simple — perhaps even simplistic. But the results were unexpected.

To my surprise, I realized I’m basically happy most of the time. My meter is usually in the 3 or 4 range. As the day flows along, it sometimes dips to a -4 or -5. Sometimes it rises to a 6 or 7. But mostly it hovers in a moderately positive range.

This threw me a little. If you ask me at a random time how I’m doing, the first thoughts that pop into my mind are complaints. Those negative thoughts are the product of childhood conditioning a long time ago. Yet today, my thoughts still tend to say “I’m a -2 today” when my actual vedana meter is usually more of a +3. I didn’t realize how different my thought content could be from my mood.

Another surprise was how much I enjoy thinking. While meditating, I often view a thought sprint as an annoyance. But when I’m thinking, the meter can go up to a 6 or 7. The thought content can be negative while the process of thinking can be positive.

Seeing how pleasurable thinking can be has made it easier to not fight thoughts. I understand the mind’s attraction to them. Rather than push them away, I can take in the pleasant vedana and release the thought content. The underlying uplifting quality can be healing if I don’t fight it. I don’t have to get lost in the content of the thoughts. That can be released. I just rest in the pleasantness behind them and let it radiate outward.

Another observation I’ve had and heard from others is what happens when vedana is in the negative range. If I see that feeling tone with dispassionate interest, the meter tends to move in a positive direction on its own. This is what happened to me when writing song lyrics on the bus so many years ago. Only now I know the actual lyrics didn’t matter. It was the quiet, openhearted observation of my inner experience that allowed tension to release and relax so that the vedana became more pleasant.

From this I’ve come to appreciate that vedana – the preverbal pleasantness-unpleasantness dimension of everyday experience – may be so subtle as to be under-noticed. Yet it may have tantalizing insights to share if we learn to listen to its moods with an opening heart and a quieting mind.

Vedana and tanha are closely related. They have different moods and styles, but often interact together. If we want to deepen our meditation, bring more peace and vitality into our lives, or simply get our selves out of the way, relating skillfully to tanha is very helpful. It’s at least as important as vedana.

Tanha is a Pali word usually translated as “craving” or “desire.” But it has a much wider range of meanings and strength than these common translations. Tanha is the intensity of wanting, not wanting, or confusion in any experience. It is felt as tension. Like vedana, it is preverbal — something we can feel directly — and can be thought of as positive (desire) or negative (aversion). It can be powerfully positive like the craving of an addict for a fix. “Positive” doesn’t mean “wholesome,” only that it is a wanting to have something. It can be gently positive, like soft yearning. It can be gently negative like “no thank you.” And it can be intensely negative like rage or terror.

Tanha is a good candidate for a mental app. Tony Bernard calls it a “Wanting Meter.” Rather than measuring pleasantness or unpleasantness, it measures the intensity of desire and aversion.

We can create a Wanting Meter in a manner similar to creating a Vedana Meter: produce a mental image of a scale that runs from powerful aversion to neutral to powerful desire. Then add numbers to the scale. That’s it.

The Wanting Meter may not need to be pre-calibrated. We pre-calibrated the Vedana Meter by thinking of various pleasant and unpleasant sensations and seeing how the Vedana Meter responded to each.

But the intensity of tanha is not tied as directly to raw sensations. For me, chocolate often produces pleasant vedana. Sometimes I crave chocolate; other times I can take it or leave it. The pleasantness of chocolate may stay the same but the strength of wanting can vary widely. An insulting remark might trigger hatred or mild annoyance. Thoughts might be fueled by a powerful craving to solve a problem or by a faint wondering. Since the intensity of desire or aversion for a specific object can vary, pre-calibrating our Wanting Meter is less effective or necessary. We can simply start using it.

As we use the Wanting Meter, we can see how close tanha and vedana are to each other. The Buddha describes this in his Laws of Dependent Origination (paticcasamuppada). So I’ll give a quick summary of how they work together and with other states.

Dependent Origination is like a line of dominos, where each domino falls to knock over a bigger domino. Each domino is an inner event. As described earlier, raw sensation (phassa) can give rise to feeling tone (vedana). If vedana is seen clearly and the tension around it is relaxed, the mind-heart becomes peaceful. Otherwise, vedana can give rise to wanting or not wanting (tanha).

If the tension in tanha is seen and relaxed, the mind returns to it’s naturally peaceful state. Otherwise, tanha can give rise to clinging (upadana).

Up to this point, each domino is preverbal and preconceptual. But with upadana, the mind shrink-wraps around the experience and gives it a name or label. Clinging is always experienced as a thought. The first mental concepts have formed. Awareness shifts away from the preverbal experiences of vedana and tanha and clings to the thoughts and concepts.

If the clinging is seen and relaxed, the mind-heart returns to it’s underlying equanimity. But these dominos are big and have a lot of momentum. Clinging can trigger thoughts, ideas, emotions and other habitual tendencies (bhava). Habitual tendencies may spur us into action. If wisdom is not strong, those actions can get us into trouble and we suffer. Bummer.

Fortunately, it’s not necessary to memorize this string of events. But they do have some implications that can be very helpful:

The Wanting Meter is not about action. It’s about desire. Actions come later in the series. Paying attention to what we do does nothing with the desire beneath it.

Thinking is considered a mental action in Buddhism. If we want a peaceful mind, stopping the action of thinking doesn’t really help. It’s the desire underneath that fuels the thoughts and actions.

Understanding this has been very helpful for me. When a lot of thoughts come up in meditation, rather than trying to stop the thoughts, I just check the Wanting Meter. If the desire to think is very faint, it’s easy to relax the tanha. Then the thoughts just run out of gas and quiet down naturally.

If the desire to think is powerful, then I just see that desire as it is. This shifts the attention away from the content of the thought back to the tension that is fueling it. As I recognize the tension in the desire, I can relax it with the Six Rs. If there is a lot of fuel (desire), it may go on for a while, but I’m doing nothing to add more fuel. Eventually the thoughts run out of gas and quiet down.

Though vedana and tanha rub elbows all the time, they are different phenomena. They even have different underlying neurochemistry. The strength of pleasantness or unpleasantness is related to the levels dopamine. The strength of desire or aversion is related to the levels of opioids. A different biological process supports each. The Vedana Meter does not dictate what the Wanting Meter will say and vice versa. They are related but not the same. Seeing each phenomenon on its own is very helpful.

As each domino falls on the next, the sense of a separate self can get stronger. Vedana sends up the first shoots. Tanha sends down roots. Clinging (upadana) sends out leaves by adding a label and concept for the self: “I want this” or “I don’t like that.” Attention shifts to the labels and concepts that are assumed to be true. The phenomena that give rise to the sense of self are not directly seen as we get entangled in the storyline.

If we’d like to get ourselves out of the way, we can’t do it effectively once the thoughts and concepts have taken over. We’re just arguing philosophy rather than directly experiencing phenomena.

But if we can recognize and release the vedana or tanha, the sense of a separate self does not come up. There is just a flow of impersonal phenomena.

The Laws of Dependent Origination articulate a series of events that lead to bummers.

If we’d like to reduce our suffering, the most effective place to do this is not with the bummers themselves but with the smaller dominos that lead up to them.

The Buddha said that the weakest link in this chain is tanha. The events before tanha can be so faint that they are hard to see. The events after tanha can have so much momentum that they are hard to stop or see beyond.

But tanha is strong enough to be seen and still small enough to be relatively easy to relax.

The Wanting Meter is very helpful in seeing tanha objectively. It exposes the strength of desire and aversion. We can feel and see it directly as an impersonal phenomena.

This allows more ease to flow through our life.

The meters are images or mental constructs. As such they are relatively course. When the mind is busy or coarse, the meters can be helpful to tune awareness into vedana and tanha.

However, when awareness is light and refined and we’re adept at recognizing vedana and tanha, the meters may be too crude to be helpful. At this “higher altitude,” mentally constructing the meters may just get in the way of seeing what we already see. So they can be dropped.

All meditation tools are like this. They are rafts to get to the far shore or greater awareness. Once on that shore, there is no need to put them on our back and carry them up the mountain. Instead we just release tension.

Copyright 2017 by Doug Kraft

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use all or part of it for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the author. Specific licensing details are here.

How to cite this document

(a suggested style): "Awareness Meters" by Doug Kraft, www.dougkraft.com/?p=AwarenessMeters.

Derek Baker, July 29, 2024

Hello Mr. Kraft,

Thank you for these wonderful tools cultivate mindfulness for these preverbal aspects to inner cognition. I'm also a scientist with an interest in neurolgy. It's interesting to think about the relationship between the neocortex and the hindbrain. I will be sure to add this to my daily meditation practice! Thanks again!

Kindest Regards,

Derek Baker