Chapter 4 from Presence

Chapters on line: Description and Table of Contents / Chapter 1: Introduction: Emerging Clear Awareness / Chapter 2: Roots of Consciousness: Primordial Affective Emotions / Chapter 4: Spectrum of Awareness / Chapter 6: Magic of Awareness: Enlightened Futility / Chapter 15: Summary: Emerging Consciousness and Twilight Awareness

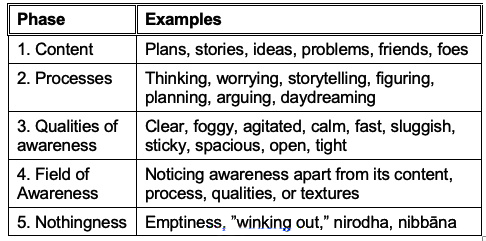

The last chapter explored relaxation and expansion. This chapter explores the Spectrum of Awareness as a practical tool for integrating relaxation and expansion into our meditation practices. The table offers a conceptual overview.

Actually, rather than a table of separate boxes, the Spectrum might be better illustrated by a gradient in which each phase blends with its neighbor.

Like most of Buddhism, the Spectrum of Awareness is a phenomenology. It’s not a philosophical or intellectual construct. And it’s certainly not metaphysics or theology. It’s a description of direct experience — phenomena — rather than ideas about experience.

The Buddha realized that if we can know what we are experiencing clearly enough and relax about it, that is the beginning of the end of suffering. So, he advocated awareness of phenomena as they are rather than explanations of what they represent philosophically.

The first phase of the Spectrum of Awareness is content. The evolutionary function of awareness is to see the content of experience and develop a map of what’s out there: bird, tree, rock, river, etc. Some objects have more charge: a guy with a spear, a dog with its teeth bared. The greater the charge, the more the mind shrink-wraps around the object(s).

As the mind-heart relaxes and expands, we may begin to notice the second phase of the Spectrum: the processes out of which the objects arise. We notice the thinking, feeling, daydreaming, and other processes the mind is engaged in doing rather than focusing only on the contents of thinking, feeling, daydreaming, and so forth.

Like the contents, the processes can also be light (musing, wondering, fantasizing) or more energized (complaining, worrying, arguing, defending). But as the mind relaxes and expands, the contents drift into the background and the processes become clearer.

As we become more aware of the processes, we may start to notice the qualities of awareness that give rise to the processes. Awareness can be light, serene, peaceful, or easygoing. Or its qualities may be more energetic: anger, fear, urgency, excitement, obsessiveness.

As we notice the qualities, the mind-heart naturally relaxes and expands. And it works the other way around as well: as the mind-heart relaxes and expands, we become more aware of the subtle qualities of awareness.

As the qualities become more apparent, we may start to notice the field of awareness itself. We may notice the effects of being aware. At the end of the last chapter I described this as analogous to taking in the field of an entire meadow rather than just zeroing in on the plants and animals in it. Or looking into a moonless night and sensing the empty space between the star rather than just the celestial objects. On a smaller scale it is liking meeting a new person and being struck by their overall presence rather than just their freckles or socks; or taking in the ambience of a crowd of people rather than just a few individuals.

We also notice the field of awareness any time we take in the quality of our awareness itself rather than just the objects we see.

If we are aware of awareness and continue to relax and expand, we may notice the nothingness out of which phenomena and awareness arise. In meditation, these first manifest as short blank spots in our attention. We may wonder if we had drifted off to sleep for a moment.

However, when we doze and come back, the mind is often a little dense or foggy. But as the mind-heart relaxes and expands, there may be blank spots followed by clear awareness (as alluded to in the subtitle of this book). In this case, it is less likely that we actually fell asleep and more likely that the mind became so relaxed that awareness itself stopped functioning for a moment. The Buddha called these blank spots nirodha — the cessation of perception, feeling, and consciousness.

When cessation is deep enough, the mind-heart that returns is not exactly like the one we once knew. The objects, concepts, and sense of self that once predominated have receded far into the background of irrelevance. This is a sign of nibbana — a topic for another time.

From the perspective of the awareness, we have relaxed and expanded from one end of the Spectrum to the other. The Buddha called this end “the extinction of suffering.”

I presented these phases starting with the one we are mostly likely to be aware of first: the content. As awareness quiets, it becomes easier to see the processes that generated that content. As the mind quiets some more, we may see the qualities that generated the processes. And so on through awareness itself and the nothingness out of which awareness arises.

Notice that philosophically we could have turned the sequence on its head and started with the formlessness out of which awareness itself emerges, and in turn out of which qualities, processes, and content emerge. We could reasonably present the opposite sequence.

And we could have presented the Spectrum without any sequence. The term paticcasamuppada is usually translated as “dependent origination” which suggests a linear series where each phase is the origin the next. But the term more accurately translates as “dependent co-arising.” The spectrum emerges whole cloth, as it were. Thich Nhat Hanh calls this “interbeing” Rather than a line of falling dominos, a better image is a web where everything is connected to everything else in a mind-boggling complexity.

But we don’t have to pick winners and losers in this debate. As I indicated earlier, the Buddha was most interested in a practical resolution of suffering. For that purpose, awareness of the phenomena is enough. The present moment contains everything we need to be free if we can see it clearly and deeply enough.

Meanwhile, as emerging awareness of the present deepens, don’t be surprised if some of our ideas about how things work get thrown overboard.

To take the Spectrum of Awareness into meditation, the general idea is to gradually shift our attention from the contents of awareness across the Spectrum. This shift is often easier and more graceful when done in small, natural movements from content, to process, to qualities of awareness, to awareness itself, to the nothingness out of which awareness arises.

The most obvious difference between various styles of meditation is the “home base” that is recommended to help settle the practice. Often it’s called the “object of meditation.” This side of enlightenment we can count on the mind wandering — sometimes a lot. When we notice this, the instructions are to return our attention to this homebase. Tension is a cause and condition that encourages the mind to wander more. The art is to return to home base without being critical of ourselves or tightening up in other ways. Instead, we relax and expand as we come back to the home base.

My favorite practice for doing this is embedded in the Buddha’s teaching of the Four Noble Truths. A slightly more elaborate version, called the Six Rs, was developed by Bhante Vimalaramsi and is particularly helpful when the mind is very jumbled.

I’ve written about these practices in Buddha’s Map and subsequent books.[Footnote 1] However, I review the most relevant parts in chapters 5 and 6 and appendix A of this book.

Regardless of what strategies we use to get the mind-heart back on the path, if it includes relaxing and expanding, it will tend to move the mind along the Spectrum of Awareness.

In the remainder of this chapter I want to explore our choice of objects for that home base and how to integrate that choice with the Spectrum of Awareness. This makes meditation more dynamic and responsive and helps wisdom and compassion arise more easily. To see this, let’s look at some of the objects that are used as a home base — the breath, metta, and objectless awareness — as well as how to make the practice more flexible and responsive to our experience.

The Breath

The breath is a widely used home base. The most obvious aspect of the breath is its content (phase 1 of the Spectrum): the actual sensations in the chest or tip of the nose.

If we notice these, it is easy and natural to open up a little further on the Spectrum to the process of breathing (phase 2): the rising and falling of the diaphragm, chest, or the subtle movements throughout the body.

If we do this, it is easier to notice the qualities of the breath (phase 3). It may feel light, heavy, gentle, tense, ragged, etc.

If we notice the qualities, it is easier to notice the subtle effects of being aware (phase 4) and perhaps even the emptiness (phase 5) out of which the breathing seems to arise.

Metta

Metta or one of the other brahmaviharas is another kind of home base. [Footnote 2] We might repeat simple phrases that express friendliness or compassion: “May I be happy, free, and filled with ease. May you be filled with delight and ease,” and so on. As we do this, we can focus on the content of the phrases (phase 1) or on the process of sending these qualities to ourselves or others (phase 2).

When I was practicing under the guidance of Bhante Vimalaramsi, he emphasized the feeling of kindness, compassion, etc. (phase 3). We might recall a time when it was strong and hold that quality in our hearts as it is radiated outward. As the qualities settle in, it is easier to notice the expansiveness of awareness itself (phase 4).

This practice is a little more difficult in the beginning than just watching the sensations of the breath or repeating a metta phrase. But when it works, the meditation goes deeper because it begins in a more profound phase. Rather than beginning with physical sensations or words (phase 1), it begins higher up the spectrum with the quality of awareness (phase 3) and quickly moves to awareness itself (phase 4). And it’s closer to awareness vanishing or “winking out” (phase 5).

Objectless Awareness

Objectless awareness is another home base, but it is unique in that it literally starts with nothing (phase 5). This is a very simple practice but very difficult because there is nothing to hang on to. We just start with a blank mind and if anything at all shows up (which it usually does), we treat it as a hindrance (nivarana) and work with it wisely and kindly.

These days my preferred meditation is just short of objectless awareness. There are many states that are right on the edge of objectless-ness. Chapter 6 (pp. 71-79) has a list of 14 such signs of clear awareness. To meditate, we start by recalling one of these and how it feels. From there, we just relax toward objectless-ness. Sometimes it’s easy to do. Other times it is impossible because there is too much static in the mind. In this case, we either work with the distractions (nivarana) or temporarily use a practice that begins in an earlier phase. Flexibility Flexibility is implicit in using the Spectrum of Awareness in these ways. When someone is first learning meditation, rather than shifting techniques, it is usually helpful to adopt a simple practice and then work with it consistently. This allows the mind-heart to settle in without the potential distraction of deciding what to do while we’re meditating.

However, with a lot of practice, we gradually become facile with techniques higher up the Spectrum. Earlier styles, such as watching content, may prevent the practice from going further. Instead, we shift up the Spectrum.

However, even with years of mastery, there may be days when there is just too much energy in our system. If we stay with subtler techniques, the mind just wanders off again and again until we become discouraged.

For intermediate and advanced practice it is helpful to be comfortable with several techniques. Then we can use the ones most appropriate for wherever the mind-heart finds itself on a given day.

Obviously, rapid shifts in practice are not helpful. Neither is sticking with something that is not working after a reasonable length of time. So, I encourage meditators who have some years under their belts to cultivate enough wisdom to recognize when it is best to stay with a given practice and when it is best to shift to a procedure in order to let the meditation practice deepen.

Having said that, the most advanced way to practice objectless awareness is to do nothing. This is both simple and difficult. If the mind is quiet, we do nothing but observe. If the mind is carrying on, we do nothing but observe. If the mind is non-observant, we notice the non-observance. The trick is to do this without migrating into the trance of thinking. Past and future fade as we quietly and openly receive the present.

Again, the core of meditation is to see what is most true from moment to moment. If we can recognize what’s arising and passing and at the same time relax and expand, the mind will clear itself.

The practice of relaxing and expanding can be very subtle and nuanced. This is what makes it so effective. It can also make it difficult if the mind-heart is agitated, unruly, stubborn, or cranky — which it is all too often.

The Buddha had a solution for this as well. And that solution is the core of the practice he taught. I’ll talk about that it in the next chapter.

1. Buddha’s Map

(2013), Meditator’s Field Guide

(2017), Befriending the Mind

(2019), and Resting in the Waves

(2020).

2. The four brahmaviharas are metta

(friendliness), karuna

(compassion), mudita

(empathetic joy), and upekkha

(equanimity).

Copyright 2023 by Doug Kraft

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use all or part of it for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the author. Specific licensing details are here.

How to cite this document

(a suggested style): "Presence

Chapter 4: Spectrum of Awareness by Doug Kraft, www.easingawake.com/?p=PresenceSpectrum"