Chapter 1 of Befriending the Mind:

Has life ever taken you to the edge of what you can manage, and then kept right on going without slowing down?

In mid-October of 1982, my wife, Erika, almost died. She was almost nine months into our second pregnancy. We were monitoring possible Rh blood incompatibility between her and the fetus. Otherwise things were healthy.

At a routine pre-natal exam, our family doctor said he wanted her to see an ob-gyn physician immediately. It turned out she had a more serious condition called preeclampsia. Eclampsia is the Greek word for lightning. That is how it comes on: fast with potentially devastating effects. There aren’t many treatment options. The only possible cure was to deliver the baby.

Fortunately, our doctors recognized what was going on. And fortunately, we were almost full-term, so the risk of delivering the baby was minimal. They sent us straight to the hospital delivery room. “No,” our doctor said. “Don’t go home to get clothes first. I’ll meet you at the hospital.”

As Erika was being prepped, lightning struck. Her blood pressure shot up to 280 over something. Organ systems began to shut down. “She’s about to have a seizure,” the doctor said.

They were able to stabilize her. It was a struggle. But in the wee hours of the morning, they were ready for an emergency cesarean section. The nurses tried to get me out of the operating room. The doctor looked at me for a moment, then turned to the nurses. “He’s okay,” the doctor said. “He’s been calm through this. He can stay.”

I was so grateful.

A short while later they took a dark mass from Erika’s body that didn’t look like anything I had ever imagined. But I knew it was our child. He took a breath and turned from grey to pink for a moment.

The operating room began to turn like a slow-motion carousel on the side of a hill. I was determined not to faint and draw attention away from Erika and the baby. I sat on a stool as they brought the baby over to a scale next to me. One of the doctors examined him. “He’s fine. Apgar score of nine.” (The Apgar is a ten-point scale used to rapidly assess the vitality of a newborn.)

The nurse wrapped him up and sent him off to the nursery so the medical team could focus on putting Erika back together.

Ten minutes later they wheeled her out of the room. The doctor looked back at me, “She’s going to be okay. She’ll be out for a while and will probably feel pretty awful when she wakes up. But she’s out of the woods. She’ll be fine.”

Somehow I found my way to the nursery. The nurses set me up in a big rocking chair. Then they brought over a swaddled baby who fit in the palms of my two hands. I was so grateful to feel his tiny body.

When our first son, Nathan, was born five years earlier, he had trouble breathing and was quickly sent off to a hospital an hour and a half away that had a neonatal intensive care unit. When I got there the next morning, he was like a hedgehog bristling with tubes, wires, and medical equipment. It was hard to snuggle with him.

So with our second son, I was so grateful to be handed a little body wrapped in nothing but a blanket.

Erika and I both liked the name Damon, but we wanted to meet him before we settled on a name.

His eyes were wide open looking up at me. I looked down at him. “You’re Damon,” I said. It felt right.

Then we were just there. Looking at each other.

After a few minutes — or maybe a few hours, I couldn’t tell — I noticed that the sky outside the window was turning pink. Dawn.

Nathan and my mother-in-law were probably waking up and wondering what was going on. I decided to go home and fill them in.

When I pulled into the driveway, Nathan came running out of the house carrying a doll by the foot. Erika and I had gotten it for him as a present. We had wrapped it up and left it with my mother-in-law to give to him when his brother came out.

I filled him in on the essentials — he had a new baby brother, it had been a rough delivery, but everyone was okay now. And we were going to the Pancake House to celebrate.

Back home an hour later I decided to take a nap before going back to the hospital. I’d been up for 30 hours. I sat down on the bed and pulled out my journal. I closed my eyes and put myself back into that nursery when Damon and I had first gazed into each other’s eyes. I recalled as clearly as I could the actual words that had gone through my mind, and jotted them down so I could tell him years later. This is what I wrote:

“Welcome, little friend, little being entrusted to our care. I just keep thinking, ‘Welcome little friend.’

“Where did you come from, you with the stars in your hair and the ocean depths in your brown eyes? Such tiny fingers. Such a large soul.

“Wherever you came from, you are here now. This is the earth, and I’ll be your daddy this time. In the years ahead, we will laugh and cry and no doubt quarrel together. We will watch our lives unfold.

“But somehow, at this moment, when your body is so soft and new to the world, we seem closer to who we truly are together. And the love in it nearly overwhelms me.

“Do you understand this? Do you know what I’m thinking? Have we met before? This feels more like a reunion than a meeting of strangers.

“How can such a little being affect me so, unless the essence is not what the doctors and nurses weigh and measure.

“There is mystery here –– something much bigger than I can capture. And I’m truly grateful for that.

“Welcome, little friend.”

The events of mid-October 1982 touched and moved me because I was so vulnerable. I wasn’t frightened. Fear requires anticipating negative consequences and choosing to fight against them. But there was no time to anticipate, and life had overwhelmed my defenses. I couldn’t have resisted if I’d tried.

I was just present, dealing only with the moment. That’s all I could manage. That’s why the doctor saw me as calm. I was incredibly vulnerable yet had no fear. Fear came later when I had time to think about all the things that might have happened.

Usually we have time to anticipate and choose how to relate to our experience. We can open a little more or shy away. But on that day, life took over and ripped me open. Thankfully.

Vulnerability has negative connotations because it can leave us feeling weak and more susceptible to hurt, grief, disappointment, depression, loneliness, failure, and more. But vulnerability also makes us more susceptible to tenderness, gratitude, love, surprise, growth, and change.

When we sit down to meditate, go off on retreat, or just contemplate life in the wee hours of the morning, what are we looking for? Perhaps a little love, kindness, peace, contentment, serenity, wisdom, insight, equanimity, joy, or awakening? None of these are possible without vulnerability.

We’d like to open up without risk, break through without breakage, awaken without being disturbed. But it’s a package deal. We can’t have one without the other because they all require vulnerability.

A yogi sent me a link to a TED talk by Brené Brown on vulnerability. She describes herself as a social scientist–researcher–storyteller. In pouring through hundreds of stories people had sent her about difficult situations in their lives, she found that those who did well with their vulnerability had heartfully embraced it. Those who didn’t do well had collapsed into guilt and shame.

As she dug more deeply, she saw that those who embraced their vulnerability felt worthy of love. Those who contracted into shame felt unworthy.

How about you? Do you feel worthy?…

Come on. We are all worthy of love. How could it be otherwise? We are worthy not because of who we are. We are worthy not because of what we do. We are worthy simply because we are. We have arisen out of this intricate weaving of matter, energy, and spirit that is the web of life itself. We are part of it all. We belong here. This is our home. We are all worthy of love because we are all a part of everything.

But the people and events in our lives may have taught us otherwise. Particularly in the West where achievement-oriented styles of childrearing too often foster self-hatred, many of us have learned otherwise. All of us probably have some unworthiness to unlearn.

It’s valuable to set aside time for this unlearning; time for rediscovering our natural, humble worthiness; time for deepening our capacities for embracing vulnerability and for opening to the grace and wisdom that come with these qualities. Such time might include quiet conversation with a friend, mentor, counselor, or trusted guide. It might include solitary walks in nature. It might include daily meditation. I have found extended meditation retreats particularly helpful because they combine all these elements.

When I go on retreat, I’m looking for a place that stirs my natural vulnerability to awakening. When I’m leading a retreat, I try to provide this for others.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t try to beat hearts open like all those encounter groups I joined years ago. I don’t schedule near-death experiences or observations of loved ones in surgery. I don’t even bring in babies to snuggle.

My retreat strategy is gentle. It begins with a quiet facility, hopefully with access to nature. It provides good food, comfortable rooms, and a gentle setting that is disarming. Rather than confront our defenses, this strategy removes distractions. It replaces idle conversation with silence. It replaces cell phones, computers, books, and entertainment with quiet.

In this setting we’re invited to confront ourselves. Over and over we’re encouraged to sit down on a cushion or comfortable chair and close our eyes. Then we’re left alone and unchaperoned with our mind.

Sometimes the mind is lovely, expansive, and sweet. Sometimes it’s crazy. Sometimes it’s blah. The hard-earned wisdom I’ve learned about deepening our connection with life is to embrace our tenderness — practice loving our vulnerability.

This may mean different things at different times. When we feel bummed, loving our vulnerability means having compassion and kindness for those tender spots. When we feel expansive or joyful, loving our vulnerability means savoring these wholesome qualities and letting them soften us. When we feel humdrum, loving our vulnerability means loving the common, ordinary, earthiness of our lives.

The Buddha hints at these qualities throughout the Sutta Nipata by saying, “You are not better than anyone else. You are not worse than anyone else. And you are not the same as anyone else.”

Your sensitivity is expressed in unique ways. Love this vulnerability.

I have found two interacting practices particularly helpful. They are a bedrock that supports the entire path. As they deepen, they unfold and shift to take advantage of what we’ve learned. I have written about these extensively in Buddha’s Map and Meditator’s Field Guide, so I’ll just offer a quick review here.

Before meditating, it is helpful to find a relatively quiet place to sit comfortably. Sit upright if possible — lounging invites the body and mind to go to sleep rather than wake up. But the posture should be comfortable. Cushions or chairs are both fine. Sitting cross-legged isn’t required. A posture that is familiar to your body will be less distracting and more helpful than one that is uncomfortable.

To start the actual meditation, remember what happiness feels like. Perhaps you recently accomplished something that left you feeling great. Perhaps it was the soft happiness of holding a small animal that cuddled into you. Perhaps it was the selfless joy of watching a child play. Perhaps it was the serenity of watching a sunset by the ocean.

All of us have felt happy at times — many times — in our lives. The feeling may vary depending on our temperament, history, conditioning, and circumstance. The flavor of happiness is not important: kindness, joy, compassion, equanimity, gratitude – any uplifted quality that has little tension in it or that naturally reduces tension.

This is where this meditation practice begins –– not so much with the memory of the situation but with the feeling itself. It’s like a glowing in the center of your chest.

To begin, put an image of yourself in your heart. Some people visualize easily; others don’t. It’s not important that you clearly visualize. Just imagine holding yourself gently in the center of your chest.

Then send yourself a wish for happiness or well-being. “May I be happy.” “May I be peaceful.” “May I feel safe and secure.” “May I feel ease throughout my day.” Any uplifted state is fine.

The phrases are a way of priming the pump — they evoke the feeling. As it arises, shift your attention to the feeling itself.

Sooner or later the feeling will fade. When it does, repeat a phrase. It’s not helpful to repeat it rapidly — this makes the phrase feel mechanical. Rather, say the phrase sincerely, and rest for a few moments with the feeling it evokes. Then repeat it again.

As you do this, three things arise in the mind-heart: the person to whom you are wishing happiness (yourself), the mental phrase, and the feeling. About 70 percent of your attention should be on the feeling, 20 to 25 percent on the person (yourself), and just a little on the phrase used to evoke the feeling.

It is difficult to force a feeling to arise — and unwise to even try. So if the feeling is not present, let 70 percent of your attention rest on your intention to send uplifted qualities to yourself. The sincerity of your intention creates the environment in which the feeling itself can arise. Sometimes this takes patience.

After about ten minutes, switch the person to whom you are sending kind wishes. Rather than sending kindness to yourself, send it to a “spiritual friend.”

A spiritual friend is a living person to whom you find it very easy to wish the best. It might be a favorite teacher who always has your highest interests at heart. It might be an aunt or uncle who always looks out for you. It might be a small child who opens your heart.

A partner is not a good choice for a spiritual friend. You may have a lot of love for him or her, but primary relationships are usually complex. For the purpose of meditation training, simple is better. For the same reason, a teenage son or daughter is probably not a good choice — those relationships have too many textures. A person you find physically attractive is not a good choice either. Physical attraction can become thick, complicated, and distracting. You want the meditation to be light, easy, and uncomplicated.

Once you have settled on a good spiritual friend, stick with that person. If you switch from one person to another, the practice won’t be able to ripen or deepen. And if you stay with one person in your meditation, the other people in your life will benefit even without being the explicit focus of your sitting practice.

So each time you sit down to practice, send well wishes to yourself for 10 minutes. Then switch to your same chosen spiritual friend.

Metta — the practice of sending kindness, well-being, or other uplifted intentions — is the storefront. It is something wholesome to occupy the mind-heart. A second practice in the backroom is just as important — if not more important. It’s called the Six Rs. It is a paint-by-the-number implementation of what the Buddha meant by right effort. These two practices work intimately together as one.

As you send well-wishing to yourself or your spiritual friend, other things will occur uninvited. Thoughts, images, sensations, and emotions waltz in. This is not your intention, but the mind has a mind of its own.

As long as you’re still with the feeling of well-wishing, kindness, or peace, don’t be concerned about these intrusions. Let them float in the background, as it were, without doing anything about them.

But sooner or later, a distraction will hijack your attention completely. You won’t see this coming. One moment you’ll be sending kindness. The next thing you know, you’re rehearsing a conversation, planning your day, reminiscing about yesterday, or otherwise attending to something other than the object of your meditation.

This is great news! Now you get to use the second meditation practice. This is a powerful practice that can only be used when the mind wanders. Now’s your chance!

The drifting mind is a symptom of tension disturbing your underlying peace. This side of enlightenment, we all have many tensions. The distraction points one out — it shows exactly where it is so that you can release it skillfully. This is so helpful.

The only trick is to release the tension wisely. An unwise way is to condemn yourself, “Oh, I can’t do this!” That criticism creates more tension and destabilizes the mind further. It’s a form of aversion. Another unwise strategy is to buckle down and try harder to control the mind. This too creates more tension and restlessness. It’s a form of greed.

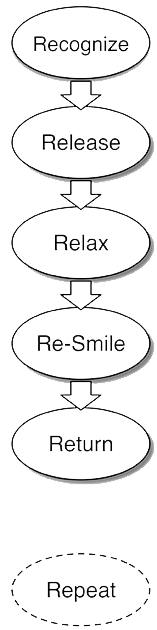

A better approach is employing a technique known as the Six Rs. These are as follows:

1. Recognize where your attention has gone. In time it will be clear that wisdom moved your attention to that particular place. What that wisdom is may not be clear right now. That’s fine. All you need to do is recognize where your attention went.

2. Release your grip on the distraction. Let it be. Don’t push it away or hold onto it. Release the hold it has on your attention or that your attention has on it.

3. Relax. Let go of any tension in your mind or body. You don’t have to search for tension like an enthusiastic detective. Just relax. That’s enough.

4. Re-Smile, or smile again. Allow a higher state — any uplifted state — to come into the mind-heart. Having a good sense of humor about how the mind drifts is helpful. So, smile.

5. Return. Now take the relaxed mind-heart and this brighter, lighter state back to your object of meditation.

6. Repeat. The repetition will happen automatically if you continue meditating — that is to say, the mind will wander again and again. If you haven’t released all the tension from a particular distraction, that’s fine. It will simply come up again until you have. You can relax in confidence that the mind-heart will let you know if there’s more to relax.

This Six-R process contains the practical essence of the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path. It is also what he meant by wise effort or effort without strain or tension. Using the Six Rs puts us squarely on the path he described.

To start, 30 minutes per sitting is adequate, though 45 minutes or more will serve you better. It takes a little time to settle into the practice. If you meditate a little longer, the practice may go deeper more quickly.

Once you get comfortable, try not to move throughout this period of time. If the mind insists on moving, Six-R the tension in the insistence. The Six Rs are very helpful in letting the mind release tension and find deeper ease.

Of course, if pain arises from genuine physical harm, you will want to adjust your posture. The way to tell if you should adjust is to notice what happens when you get up from sitting. If the pain goes away very quickly, it was probably not caused by anything harmful. If the painful feeling returns when you sit next, try to remain still and Six-R the tightness that arises around the pain. If, on the other hand, when you get up the pain lingers, it is best not to sit in that posture in the future.

The Buddha saw that craving or tightness is the root of all suffering. It also gives rise to distractions. So softening the tightness goes to the core of his teaching and practice.

When we sit down and close our eyes, it’s hard to know what will show up in the mind-heart field. Unwelcome phenomena are traditionally called “hindrances.” The Six Rs are a wise response to them. However, whether we’ve been meditating for five minutes or 50 years, hindrances are likely to continue to arise. How we relate to them often shapes our entire meditation practice. So in the next few chapters, we’ll have a look at ways to befriend these intrusions.

Copyright 2019 by Doug Kraft

This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. You are welcome to use all or part of it for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the author. Specific licensing details are here.

How to cite this document

(a suggested style): "Vulnerability" by Doug Kraft, www.dougkraft.com/?p=BefriendVulnerable.