Copyright © 2015 Doug Kraft, All rights reserved.

This has been reformatted for the web. It’s also available in pdf format.

“Metta-panna” means “kindness and wisdom.”

Half a dozen years ago I began training with a monk, Bhante Vimalaramsi, who had combed through the earliest recordings of the Buddha’s talks to find what the Buddha had actually said about meditation. Bhante set aside all he had learned from the commentaries and shaped his meditation to follow only the Buddha’s guidance. He found a simple, elegant, and extremely effective practice. The Buddha was a gifted meditation teacher – perhaps the best the world has known.

When I began teaching this style of practice, meditators asked me, “What do you call it?” I said, “The Buddha’s meditation.” They said, “That’s not helpful. There are many practices called ‘Buddhist meditation.’” They wanted a more specific name.

Gradually I began calling it “metta-panna” or “kindness and wisdom meditation.” (Many of Bhante’s students call this practice “TWIM,” which stands for “Tranquility, Wisdom, and Insight Meditation.”) It uses two tightly integrated practices: one cultivates kindness, the other cultivates wisdom.

Kindness without wisdom is not kind. Wisdom without kindness is not wise. So metta-panna does not refer to separate qualities that have been yoked together, but to two ways of viewing an awakened mind-heart.

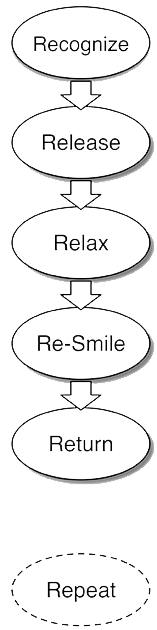

Similarly, metta-panna meditation uses two practices that intimately support one another. The first practice generates metta – loving kindness and other wholesome qualities. As you meditate, hindrances will soon grab your attention. The second practice allows you to see clearly what hijacked your awareness, release it, relax, smile, and return to generating metta. We affectionately call this second practice “The Six Rs”: Recognize, Release, Relax, Re-smile, Return, and Repeat as often as needed.

Used together, these practices gradually reveal not only the distraction, but what caused it and what caused the cause. As you relax these causal links, the heart becomes peaceful and the mind becomes clear: metta-panna.

Sri Nisargadatta once said, “Wisdom says I am nothing. Love says I am everything. Between these two, my life flows.”

Life is flow, change, and motion. Death is stasis. The Buddha did not recommend trying to cultivate permanent states of happiness, peace, clarity, or anything else. States of consciousness, like everything in the world, are impermanent. They come and go.

So the Buddha’s meditation is not about trying to control the mind-heart, but about remembering to observe the flow of the mind’s attention. This patient observation cultivates clarity, peace, and wisdom: metta-panna.

“Jhana” means “stage of meditative knowledge.” It’s not something you can be told about or figure out. It’s knowledge you gain through direct experience.

Imagine hiking up a high mountain. You experience many things: the terrain changes from forest to alpine meadows to craggy rocks; the view becomes increasingly panoramic; the thinning altitude affects your breathing; the exertion affects your body; the temperature varies. Before departing, you may figure out that these changes will occur. But those calculations are a dim substitute for embodied experience.

Similarly, jhanas are stages of embodied knowing. Jhanas are not states of consciousness, though states are associated with each. They aren’t particular perspectives, though your views of life will shift. They aren’t a specific practice, though the way you practice will change. Jhanas are clusters that include phenomena, perspectives, stages, qualities, practices, and more.

A forest is very different from a meadow. But the transition from one to another is not a sharp line. Similarly, the movement from one jhana to another is not always dramatic. Nevertheless, jhanas provide useful markers to understand where you are on the mountain and what to do next.

If you have a trustworthy teacher, understanding what jhana marker is nearest is not important – all you need is the teacher’s guidance. If you don’t have such a guide, then ascertaining what jhana you are passing through can help you locate yourself on the Buddha’s Map and guide you along the way.

I learned the jhanas as eight numbered stages and still present them that way. Traditionally, they are described as four jhanas and four bases as shown below.

Number: Name / Base

One: [no name]

Two: [no name]

Three: Equanimity with Body

Four: Equanimity without Body

Five: Base of Infinite Space

Six: Base of Infinite Consciousness

Seven: Base of Nothingness

Eight: Base of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception

This booklet offers an overview of this meditation practice: it provides the bare-bones instructions.

If you are new to this practice, this booklet gives you a feel for how it works. It also introduces you to each jhana. As your practice unfolds, the Buddha’s instructions shift to take advantage of your deepening equanimity and clarity.

If you are an experienced student of this style, this booklet gives you some quick reminders of those essential instructions as you move along.

For a more complete description of the practice, see Buddha’s Map, Breath of Love, Moving Dhamma, or the many dhamma talks by Bhante Vimalaramsi found at http://www.dhammasukha.org. The beginning instructions can also be found in more detail in the booklet Buddha’s Map: Beginning the Journey. There are also supporting talks, articles, and videos at http://www.easingawake.com.

The best preparation for meditation is to smile whenever you think of it. Smiling helps calm and open the mind-heart. You can hold the smile on your lips, in your eyes, or in the heart.

Before starting this practice, choose a spiritual friend. A spiritual friend is someone who is alive and someone for whom it is relatively easy for you to wish the best. Your friend should not be a partner or an adolescent daughter or son. You may have much love for him or her, but those relationships can be complicated. For meditation purposes, it is best to choose a simpler relationship. For similar reasons it is best to choose someone of the gender for which you are least likely to have sexual feelings.

A few examples of good spiritual friends include a teacher who has your best interest at heart; an aunt, uncle, or grandparent who always looks out for you; or a kind friend you can always trust.

Once you have settled on a spiritual friend, you will stay with them throughout the early phases of your practice. It is not helpful to switch spiritual friends from sitting to sitting.

Find a place to meditate that is relatively secluded: quiet, no phones, no interruptions, and comfortable seating. While the perfect location is not possible, it helps to do what is reasonable to be comfortable and quiet.

Posture, ultimately, is unimportant. There is nothing better about sitting with crossed legs versus sitting on a chair. So sit in a posture that is relatively comfortable and relatively upright. Once you settle into meditation, it is best to not move. The urge to move should be Six-R'd (the Six Rs are explained on the next page). When you have to move, it is better to get up and do walking meditation than to wiggle around and try to continue sitting.

To generate metta, begin with simple phrases: "May I be happy." "May I have ease." "May I feel joy." "May I feel safe." "May I be comfortable." "May I know kindness." Any uplifted state is fine. The phrases are used to "prime the pump" – to generate some feeling of uplift. Once the feeling arises, it becomes the primary object of meditation. Seventy-five percent of your attention goes to this feeling. Twenty percent goes to the person to whom you are sending metta. And five percent – a very small amount – goes to the actual phrases.

Send the feeling of metta or other uplifted states to yourself or your spiritual friend (see detailed instructions in the First Jhana section). Rather than send the feeling, some people find it easier to imagine themselves or their spiritual friend in their heart and surrounding them with kindness, ease, joy, or well-being. Either way – sending metta out or surrounding the person in your heart with metta – is fine. Use whatever method is easiest for you.

Say a phrase silently no more than once per breath. If the feeling of metta or uplift is strong, use the phrase less often. The phrases need not be synchronized with the breathing. Repeating the phrases mechanically or quickly is of little value. Choose wording that works for you so that you can say the phrases sincerely.

Thoughts, sounds, physical sensations, and other distractions will inevitably arise. If some of your attention remains with the feeling of loving-kindness or with your spiritual friend, just ignore the distractions. They are not a problem. Don't be concerned about them.

However, when a distraction completely hijacks your attention, use the Six Rs: Recognize (see and know where your attention went), Release (let the distraction be there without holding onto it or pushing it away), Relax (soften the body, emotions, and mind), Re-Smile (bring in an uplifted state; if none feels natural, then raise the corners of the mouth in a half smile), Return (bring this relaxed and uplifted consciousness back to the object of meditation), and Repeat (know that it is normal and natural to use the Six Rs many times in the course of a sitting).

Sometimes the practice gets bogged down in grief, remorse, or discouragement or comes to a standstill for no clear reason. This may happen at any phase of the practice. It’s an indication that forgiveness may be helpful.

The forgiveness practices uses phrase like “I forgive myself for not understanding,” “…for making a mistake,” “…for harming myself or someone else,” “…for not following my own ideals,” or other phrases that resonate with you. Repeat a phrase or two slowly until you feel the feeling itself. Then radiate that soft acceptance to yourself. If the mind wanders, Six-R the distraction and return to a forgiveness phrase.

After forgiving yourself for a while, the mind may shift to a person who hurt or abandoned you. If so, shift the phrases to “I forgive you for not understanding,” “…for making a mistake,” “…for harming,” or “…for not following my values.” Don’t get involved in the story about what they did. Just say a phase or two sincerely until you really feel it.

After a while, the mind may shift to someone you hurt or abandoned. Imagine them saying to you, “I forgive you for…” Allow the feeling to soak in.

This brings the practice full circle from forgiving yourself, to forgiving another, to being forgiven.

If the forgiveness practice itself gets stuck or doesn’t work, it may be because of subtle attachment or aversion. Forgive yourself and release the attachment gently.

During the day you can deepen this practice by forgiving yourself for everything: dropping something, letting the door slam, losing your keys, getting annoyed on the phone, getting distracted…everything. This helps soften an overzealous inner critic and allows you to relax into a kind embrace.

After a few days, or a few weeks, you’ll find you’re living with more kindness. The forgiveness may not be needed. You can then return to the regular metta-panna practice.

To begin, sit comfortably in your secluded space and send metta (or any uplifted feeling) to yourself. Alternately you can place yourself in your heart and surround your heart with metta. Do it sincerely. If you are unhappy, the wish that you feel happiness can still be very sincere. That's all that matters.

Send this well-wishing to yourself for about ten minutes. Then send it to your spiritual friend for the remainder of the sitting.

It is best to sit for at least thirty to forty minutes. More is better if you can do so without strain.

As your practice develops, at some point a feeling of genuine joy will arise. It may be very short in duration, or it may linger for a longer time. This feeling quiets into happiness. Happiness is similar to joy but has less energy and more spaciousness. Happiness in turn quiets into peaceful equanimity. Equanimity can be so subtle that it fades from awareness.

The cycle of joy to happiness to equanimity is a sign of the first jhana. The cycle may pass through and fade very quickly. That's fine. With patience, it will return. Meanwhile, know that you are making progress.

It is not necessary, however, that you know what jhana you are in. You may not recognize them even when you’re in them because words do not adequately describe the actual experience: the jhana may not feel exactly as you expect it to feel. All that is important is sending metta or well-wishing, and Six-R-ing distractions. Everything else will take care of itself.

With practice, the cycle from joy to happiness to equanimity lasts longer. Perhaps the happiness or equanimity lingers for a while without fading. Distracting thoughts arise less often and less insistently. It becomes easier to Six-R. You may notice a confidence that the practice really works.

These are signs of the second jhana. It is not a distinct break from the first. Rather it is a deepening of joy, happiness, equanimity, and confidence and a lessening of distractions. There are still plenty of distractions – they just are not as powerful.

You may find that the phrases begin to feel coarse or awkward: the well-wishing flows naturally, and the words seem less helpful. If so, it's okay to drop the phrases. You still have the person and the feeling of the words in the mind-heart: you continue to send metta to them but do so in inner silence. This is called "noble silence."

Some people find at this stage that sending metta to themselves first and then remembering when to switch to a spiritual friend seems to keep the practice from going deeper. In the second jhana, it is okay to just send the loving kindness to your spiritual friend. You will be included in the feeling just by sending it out. You don't have to keep purposely sending it to yourself for the first ten minutes.

However, if you sense that it would be of value or uplifting to spend some time sending it to yourself first, that is fine as well.

As your meditation deepens, joy arises less often or may not arise at all. Rather than going through the cycle from joy to happiness to equanimity, you find there is just equanimity. The feeling is strong and tangible rather than elusive as it was in the beginning. It is not uncommon for some meditators to think there is something wrong with their practice because there is less joy. For other meditators, joy shifts from a bright and relatively coarse feeling to a broad, pervasive sense of peace.

You find you naturally want to sit longer and that there are longer stretches without distractions – or at least without distractions strong enough to capture your attention.

These are all signs of the third jhana.

The shifts from the first to the second to the third jhana are not distinct. Often there is no sudden shift of energy or feeling – just a steady deepening. If you are working with a meditation teacher, they may not hint at what jhana you are in even as they adjust instructions. Worrying about which jhana you are in is not helpful. Just take care of the practice, and the practice will take care of you.

As you continue to relax attentively, your body becomes so tranquil that physical sensations fade. At first it may just be in one area of your body – perhaps you notice no sensations in your hands. However, if you move them slightly or direct your attention toward them, you feel them. Similarly, sounds may fade into the distance. Perhaps you don't notice them at all unless you think about them. Or perhaps they do not disappear but seem far away. They have less capacity to disturb you.

Meanwhile you are sitting for longer stretches. And during your best sitting, you are staying with your object of meditation, without drifting, for longer periods of time.

You are in the fourth jhana. According to the early Buddhist texts, you have become an advanced meditator.

There are a number of shifts in the practice with this jhana. Your equanimity is so powerful that your teacher (if you have one) is less concerned with you wondering about which jhana you are in. She or he may speak now more openly about the jhanas.

Since the body tends to fade from awareness, it becomes difficult to send metta from the heart because you have so little physical sensation. You may find yourself sending it more from the head or the crown of the head. Or your teacher may invite you to try that.

At this point, your teacher may invite you to use several different practices. If you don’t have a teacher but sense you are in the fourth jhana, you may engage these practices on your own. The first practice is to send metta or well-wishing to several different spiritual friends. You do this until you can see each of them smiling. Then you shift to another friend.

When you've done this for several people, send it to other significant people in your life, including family members. If some of these are difficult for you, skip them for now and come back to them when you get to the last group of people.

When all of them have smiled in your mind’s eye, send metta to several neutral people.

Finally send it to the people you know personally who push your buttons, irritate you, or who you find difficult. It’s important not to get involved with the storylines with these people. If the practice gets tough, come back to a neutral person until the metta flows easily, then shift back to the difficult person. Once you can see them smiling, you are done with them in this practice.

When you have done this practice for all the significant people in your life, send metta to all beings in all six directions. At the beginning of each sitting, it helps to get a feel for the directions by doing one direction at a time: in front, behind, to the left, to the right, above, and below. After you have a good sense of the six directions, you send out well-being to all beings in all directions all at once.

When you can do this, your equanimity is indeed well established. From here on, you continue to send out kindness, joy, well-being, or other uplifted qualities in all directions and to all beings.

Some of the traditions refer to only four jhanas with the fourth having four different "bases." I find it simpler to just refer to the bases as the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth jhanas.

In the fifth jhana, a vast feeling of spaciousness arises. This jhana is called "the base of infinite space" and is described as a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere. It feels as if it continues to expand, though it is already infinite. You send out spaciousness in all directions.

The feeling of metta may shift subtly – it becomes a little softer or more comforting. The texts refer to this as compassion.

As you relax into spaciousness, there are moments when there seems to be nothing going on – there are gaps in your awareness. Or there may be periods of deep stillness, or blinks when everything stops for a fraction of a second. Your consciousness is so relaxed that none of this is disturbing. It feels natural. You are seeing consciousness itself arise and fade.

This is the sixth jhana. The field of awareness may feel deeply and quietly joyful. It is called the “base of infinite consciousness.”

The mind-heart’s attention tends to be drawn to feelings, sensations, and thoughts more than gaps in awareness or moments of deep stillness. So in the sixth jhana it helps to gently direct your awareness into these gaps or deeply peaceful places.

When your awareness goes into these gaps, you find yourself in the seventh jhana. Here you experience longer stretches where awareness remains on the object of meditation – sending out equanimity, spaciousness, peace, and well-being. The distractions that do arise have nothing to do with anything outside the mind itself. You may notice pushes and pulls, various kinds of energies, moments of peace, and moments of restlessness. But there are no thoughts about what's for dinner or how to make the next tuition payment. "Outside" references have faded.

At this stage your awareness is very refined and subtle. It may not seem so because there are still many disturbances – but they are all internal. The seventh jhana is traditionally called "the base of nothingness." There is nothing going on related to the "outside" world, but there is a lot going on inside. I call it “no thing-ness” because there are no external objects.

In the seventh jhana it is particularly helpful to pay some attention to the seven awakening factors. The seven include three energizing factors (joy, investigation, and energy), three calming factors (tranquility, collectedness, and equanimity), and mindfulness. If one factor seems to be weak, you can gently ask that it be strengthened to bring the mind into balance.

In the seventh jhana, Six-R everything even if the distraction has not completely captured your attention. In earlier stages, it is not wise to attempt this, because there are so many coarse distractions that Six-R-ing everything generates restlessness from doing too much. But in the seventh jhana, you have enough peace that it helps to Six-R things that have not completely captured your consciousness. And by now, the Six Rs should be automated: they are a deeply conditioned habit done with little effort. They all flow together in one motion rather than six separate phases.

Be sure that ease, well-being, or metta continues to flow out from you in all directions. It may flow on its own without effort – which is fine. But if it’s not flowing on its own, gently send it out until it flows by itself.

It is difficult to describe the highest jhana because the mind-heart is so relaxed that ordinary perception and consciousness fade. It takes a small amount of tension to remember what you experienced a moment ago. It takes a tiny bit of tension to perceive what is going on now. So as consciousness relaxes deeply and subtly, normal perception fades. You enter the realm called "neither perception nor non-perception."

In this jhana it is common for meditators to not be clear about what’s going on in their practice. They may wonder if they can be both asleep and awake at the same time because it feels like falling asleep while remaining aware.

In the eighth jhana, you cease all meditative effort except to Six-R anything that arises. Otherwise, you simply get out of the way and let the mind itself run the show.

If your progress seems to get stuck, you can ask intuitively what adjustments might help and follow that guidance. It helps to cultivate intuition.

There will be moments where everything is gone. You won't notice those moments until you come out of them. I call them "winking out" – short moments of gently blacking out. My Thai teacher, Ajahn Tong, called them "peaceful cessation." There are differences in the traditions and among teachers about when these periods of winking out are just part of neither perception nor non-perception, when they are true cessation (nirodha), and when they are nibbana (nirvana).

In practical terms, what you call them is not important. When you come out of one, reflect for a moment on what was going on during the winking out. Sometimes you'll recall a lot or a little. In that case, Six-R what you recall even though it has passed. Other times, reflecting on what happened feels like looking into a black emptiness. In that case, just continue on meditating.

When the winking out is true cessation or nibbana, when you come out of it, the flow of Dependent Origination will be clearer than ever: you see easily how states lead from one to the next. Just notice this. Sometimes the pervading joy can be very intense even while it is serene.

Once you are established in the eighth jhana, the instructions stay the same until full awakening. You will go into short and then longer periods of nibbana followed by clearer and clearer seeing of Dependent Origination. These times in nibbana will help you move up through the various stages of enlightenment until you reach full liberation.

Exploration of these higher insights and of full awakening is beyond the scope of this booklet. But a few suggestions may help: